Semiconductors are the basic building blocks of microchips. These technological wonders are built into everything from light bulbs and toothbrushes to cars, trains, and airplanes, not to mention the vast array of electronic devices that have become essential to many people's daily lives.

The chip-making industry in the 21st century is said to be “at least as geopolitically important as oil in the 20th century.” But semiconductor manufacturing requires large amounts of water to cool machines and keep debris from sticking to wafer sheets, and the growing climate emergency is putting the industry at risk.

Despite the dependence of industry on water, little attention has been paid to how changing environmental conditions affect it. Journalists and think tank coverage tend to overlook climate as a risk factor to the future of the industry.

But there are signs of trouble both globally and regionally. For example, Taiwan, which produces about 90% of the world's most advanced semiconductors, has been suffering from a severe drought since 2021.

The drought is so severe that Taiwanese farmers are being paid to keep their fields fallow and supply water that would otherwise be used for agriculture to semiconductor manufacturing factories. Taiwanese manufacturing plants have even had to resort to trucking water from one basin to another to alleviate water shortages.

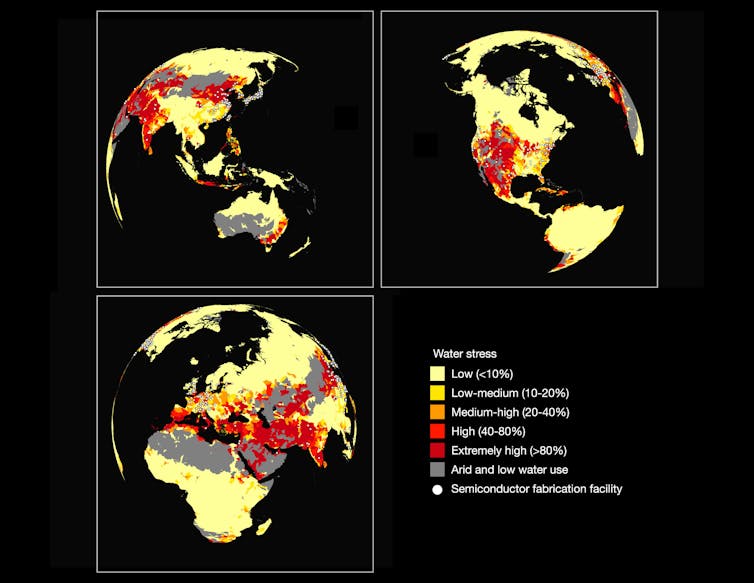

Publicly available data on water stress caused by climate change, when combined with data on the location of existing, planned, and announced semiconductor manufacturing facilities around the world, all point to a pattern of global concern for the future of semiconductor manufacturing. is showing.

looming water shortage

Regardless of the climate change scenario considered, whether optimistic, business-as-usual, or pessimistic, at least 40 percent of all existing semiconductor manufacturing facilities will be under high or very high water stress by 2030. It is located in a watershed that is expected to face risks of

High-risk watersheds are watersheds where between 40 and 80 percent of the total renewable surface and groundwater available for all purposes (irrigation, industrial, domestic, etc.) is used. Extremely high-risk watersheds are those where more than 80% of the combined renewable surface water and groundwater is used.

(Josh Lepowski)

Many of the concerns recently expressed regarding semiconductor manufacturing frame the issue from a geopolitical perspective, particularly regarding interstate rivalry between China and the United States.

Both the United States and Europe have announced large-scale government funding for the semiconductor manufacturing industry, particularly to bring back facilities for companies that have spent decades establishing manufacturing capacity outside of these regions. However, all manufacturing facilities announced or under construction in the United States and Europe are located in regions already facing significant water stress.

Intel, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) and Samsung are all building new facilities in the southwestern United States, an area that has officially been in drought since 1994. In 2021, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation issued the first-ever deficiency declaration for Colorado. river basin.

Read more: Global semiconductor shortage highlights a worrying trend: A small and declining number of the world's computer chips are made in the United States

Future climate change scenarios suggest that more than 40 percent of all new semiconductor manufacturing facilities announced after 2021 will be located in watersheds that are likely to experience high-risk or very high-risk water stress scenarios. I am.

Simply put, climate change and water scarcity pose short- and long-term risks to semiconductor manufacturing.

Current state of the industry

Semiconductor manufacturing facilities require billions of dollars of investment. When a local water problem arises, we don't just take a facility from one location and install it somewhere else.

While the future of the sector may be alarming, total water stress risk is only part of the picture. The importance of a particular node in the global semiconductor production network is another important factor.

For example, TSMC is widely known as a world leader in manufacturing advanced semiconductors for companies such as Apple, Nvidia, and Cerebras. However, TSMC only has three manufacturing facilities in Taiwan for these companies. This makes the global production networks that manufacture these technologies extremely vulnerable. Semiconductors, especially cutting-edge semiconductors, rely on a network of a small number of facilities like TSMC.

(Shutterstock)

Customers of these facilities cannot easily switch to another supplier in the face of disruption, so problems at a single facility can spill over into the global supply chain. As we experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, this could impact a variety of products that use semiconductors.

Major semiconductor manufacturers such as Intel and TSMC claim they are serious about water management. But their own company's report suggests there could be trouble down the road. Despite investing in water reuse and recycling, TSMC expects to be able to supply only two-thirds of the daily water consumption needed at its Taiwan-based facility. .

Intel, on the other hand, claims to be achieving net water usage across its manufacturing network. However, the company only manages this outcome by calculating water surpluses at its sites in one part of the world and water shortages at its facilities in other parts of the world.

An uncertain future ahead

Overcoming the risks of chronic water stress in the semiconductor industry resulting from the ongoing climate emergency will not be easy or cheap. Conflicts already exist between the industry and other water users.

Even if individual companies make significant improvements in water use efficiency, these efforts do not automatically translate into system efficiency for the entire semiconductor production network. And no amount of efficiency can overcome the problem that the water needed for semiconductor manufacturing is also needed by other users.

By reconsidering the location of future facilities that have been announced but not yet built, it may still be possible to avoid some of the worst consequences of future water stress lock-ups in the sector.

Without safe access to large amounts of water, there would be no semiconductors, and without semiconductors there would be no electronics. The climate emergency is a major driver of water stress now and in the future. Can the tech industry cope? That remains to be seen.