CEO turnover rate broke records in 2024, up over 20% at S&P 500 companies compared to the previous year. In the middle of 2025, it doesn't look that good. Early indicators point to benchmark indexes that exceed those numbers this year as CEO tenure continues to maintain a short-term pressure, increased volatility, increased cultural change and a rapid pace of change.

Corporate Board Members We asked nearly 100 board members about the increased risk for some of the largest public companies in the United States (over $1 billion in annual revenues). The response was surprisingly unflinching confidence.

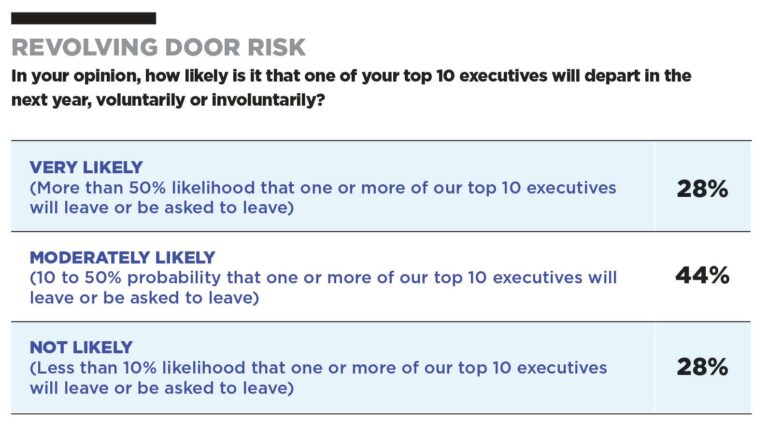

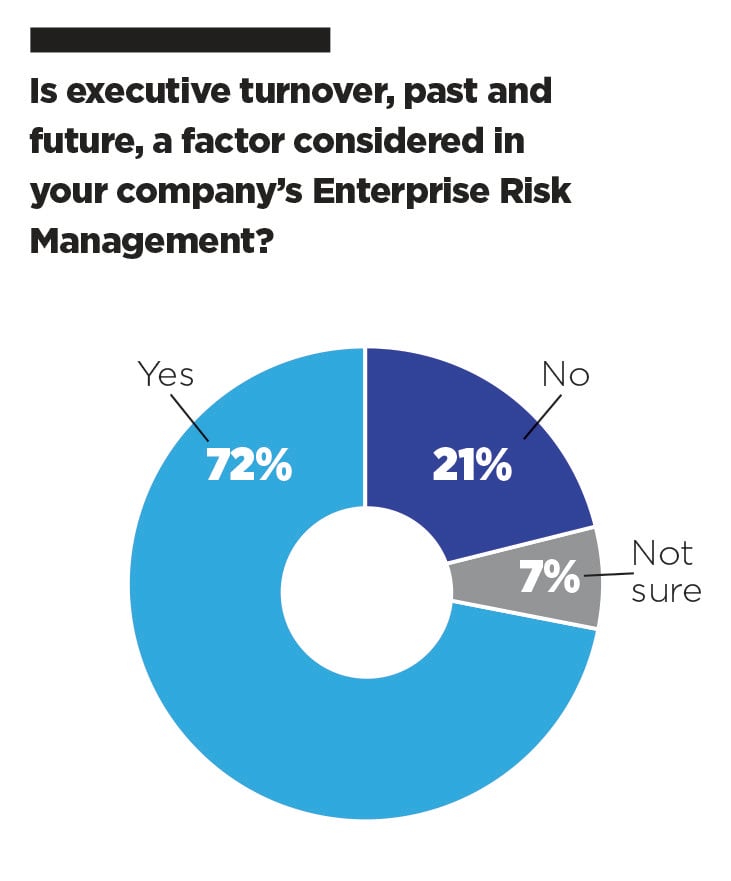

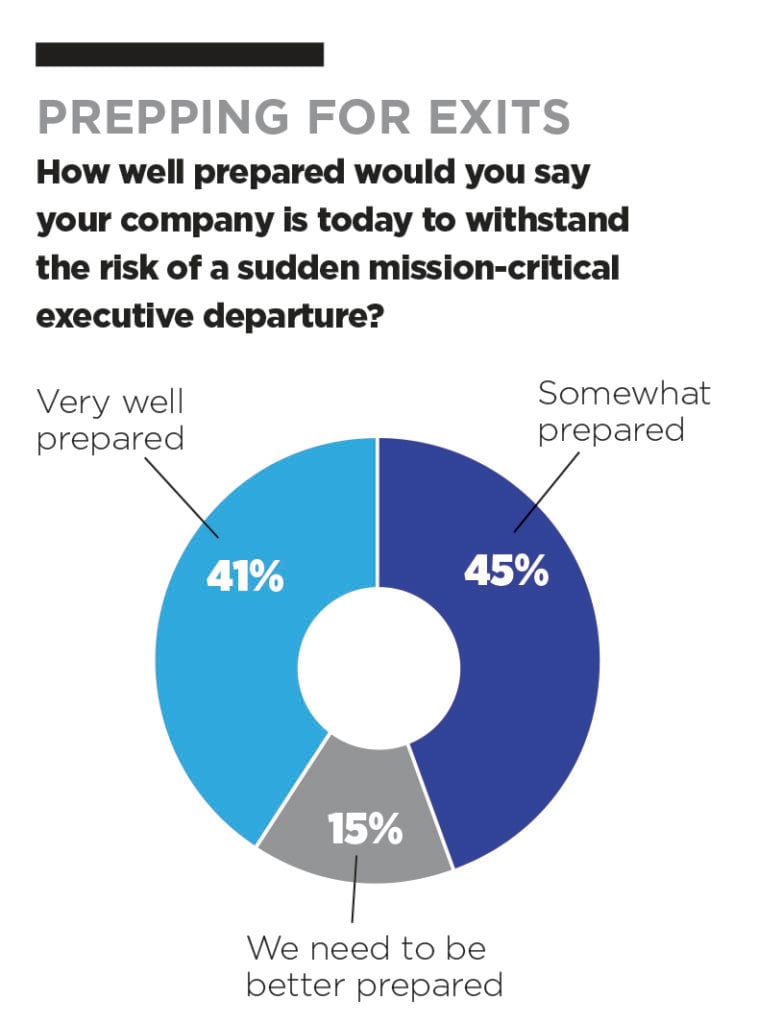

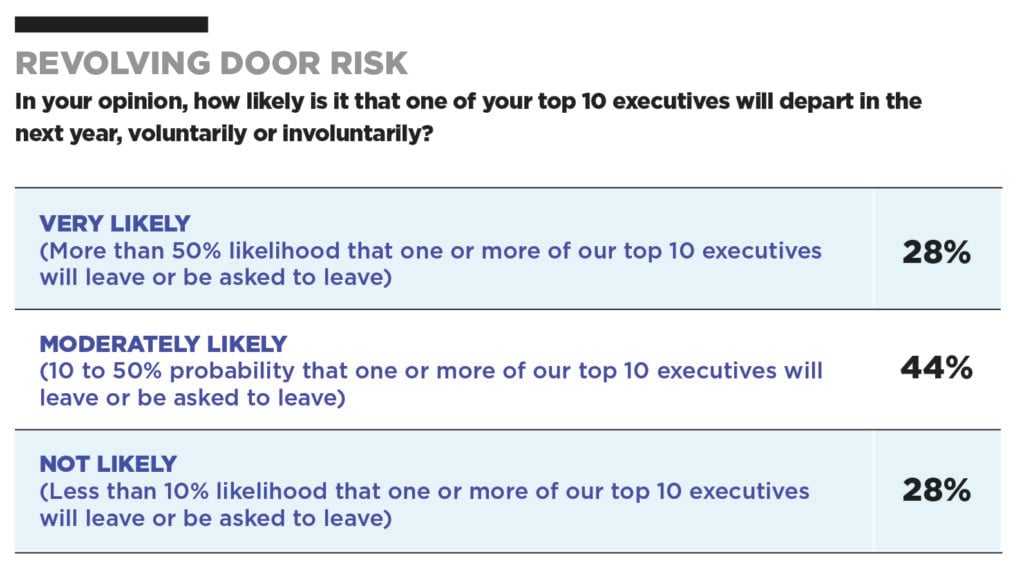

On the one hand, directors acknowledge the trend. Half of those voted said they worked on boards where CEOs or mission-critical executives suddenly departed. However, almost three-quarters (72%) believe this is unlikely to happen again in the next two years, valuing the probability of this being below 50%. And when asked about their preparations, even if this happened, 86% said they were certain they were prepared to maintain a hit without causing any damage to performance or operations.

Gaby Sulzberger, who has joined the boards of MasterCard and Eli Lilly and chaired Whole Foods Board from 2002 to 2017 Amazon acquisitions, said the high level of confidence in the response is a direct indication that the board is taking this risk and taking it seriously. “We go through a very strict process and do detailed reviews of important people, not just CEO succession, but key people, whether it's C-Suite or reporting in person,” she says. “There's a formal process and an informal process, and we'll talk about the CEO and his senior team, and where he sees the risks, where he's concerned and how he thinks about it. It's hard to think of a more important topic.”

But even committees with robust succession planning processes can struggle to manage a smooth transition after an unplanned exit, Marcia Avedon is on the board of directors of public sight, Cornerstone Build Brands and Generack Holdings, a veteran succession planning expert who serves as HR executives for major companies such as Train Technology. “We have a lot of unplanned unplanned sales at C-Suite right now, and I think there will be years when this is true,” she says. “Currently, companies are doing this process. They have succession plans and even have emergency names on paper. But I have been on board for 20 years from my board experience, so reality and what's on that paper aren't always lined up.”

Furthermore, she says the board cannot lose sight of the risk of external events that force unexpected pivots. “If the board is happy with the CEO, there is no risk-sense concern as much as most,” she said. “But who thought we had a global pandemic in 2020? That existential risk, something scary happens, people just don't think it's going to happen.”

Enhance inheritance

Directors agree that annual review of succession plans is a general best practice among boards. Jennifer Tehada, CEO and Chair of Pagerduty, where NYSE is on sale, and NOM/GOV Chair of the Este Award Maker Committee, can further strengthen the board by strengthening stress testing against potential pivots in a strategic direction and trends in awakening across the market. “How is your market changing? What is the rate of change? So how should you plan leadership, which is a complement to CEOs as well as CEOs?” she said.

Includes AI. The rapid pace of AI adoption is changing the way businesses are approaching benchbuilding and succession planning. “If you have CEOs who have no technical background for leadership roles in key brand business, you'd better have a very strong technical leader with them,” says Tejada. “For example, if you're a business that's actually trying to migrate and take advantage of the benefits of AI and need to make changes to your skill set, you might need to bring in people who have less commercial experience but have more research experience or don't fit the traditional Readynow executive style.”

A staggering successor based on the development stage can also help the board avoid many headaches in the event of an emergency inheritance event, says Avedon. “We've seen a wide array of long-term candidates for C-Suite locations, but no one is nearby. It's not a good situation when something happens inevitably.

Ideally, the board should identify potentially prepared successors, even if they are not a long-term top candidate. “If someone is developing, will they be on the list for a year or two and unexpectedly open up that role?” Avedon asks. “The boards need to get close enough to developing their successors to say, 'Are they fully prepared?' When a discussion of talent reviews takes place on the board, you have to ask, “If that happens, will we put him or her in?” That's an important question. ”

At any time, Tejada has two or three leaders on his team, who fully understand the business, understand the finances, touch all stakeholder groups, including the board of directors, and intervene in if something happens. For many boards, that might mean intervening with the board chair as interim CEO, but she warns against relying on people with busy schedules. “I often look at these emergency succession plans, but every emergency backup has a day's work. How does that work? Are they trying to stop the current gig?”

Beyond departures or unexpected accidents, the board must be able to act promptly when the market seeks sudden change at the top. This means having a NOM/GOV chair that is not afraid to make changes if you need to. “The board hates the change in CEOs,” Tejada says. “It's a high risk, so if someone in the NOM/GOV role, if change is needed, whether it's a reactionary or positive change, they'll lead the committee, lead the committee or lead the CEO. They'll put someone in the NOM/GOV role, not leading a lot of leadership transitions as operators.”

Reduce the risk

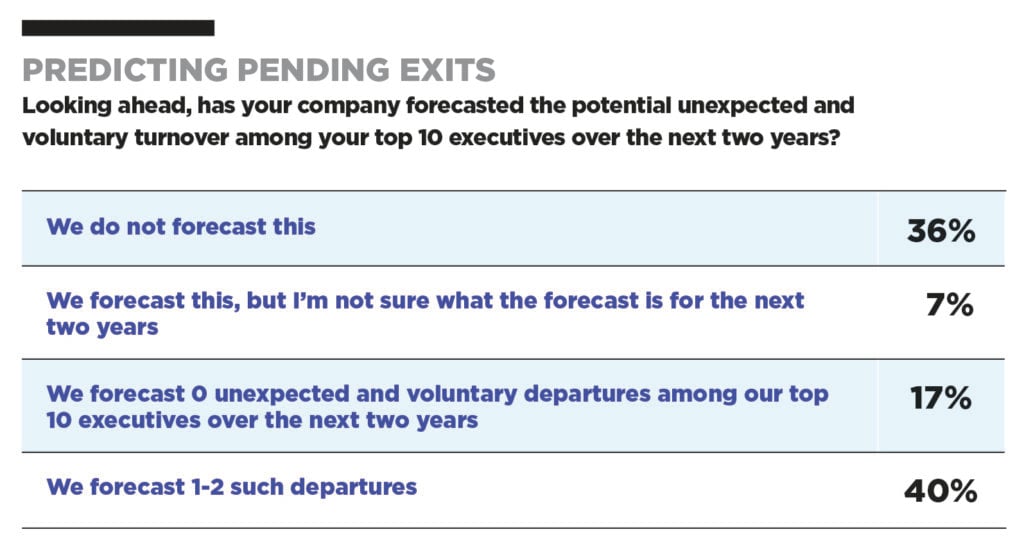

It is always desirable to work on reducing risk rather than responding to it in a crisis. At the very least, the director agrees and an annual review of succession plans is essential. It usually involves revisiting the candidate's successor list and assessing their progress and continued fit into the role they tapped, but directors are divided into values predicting risk in a few years. According to the survey, 36% say the company has no forecasts of executive sales risk at all, while another 7% say they don't know what that forecast is while they do. That is, 43% of board members oversee inheritance without clear data on the actual risk of losing these key individuals.

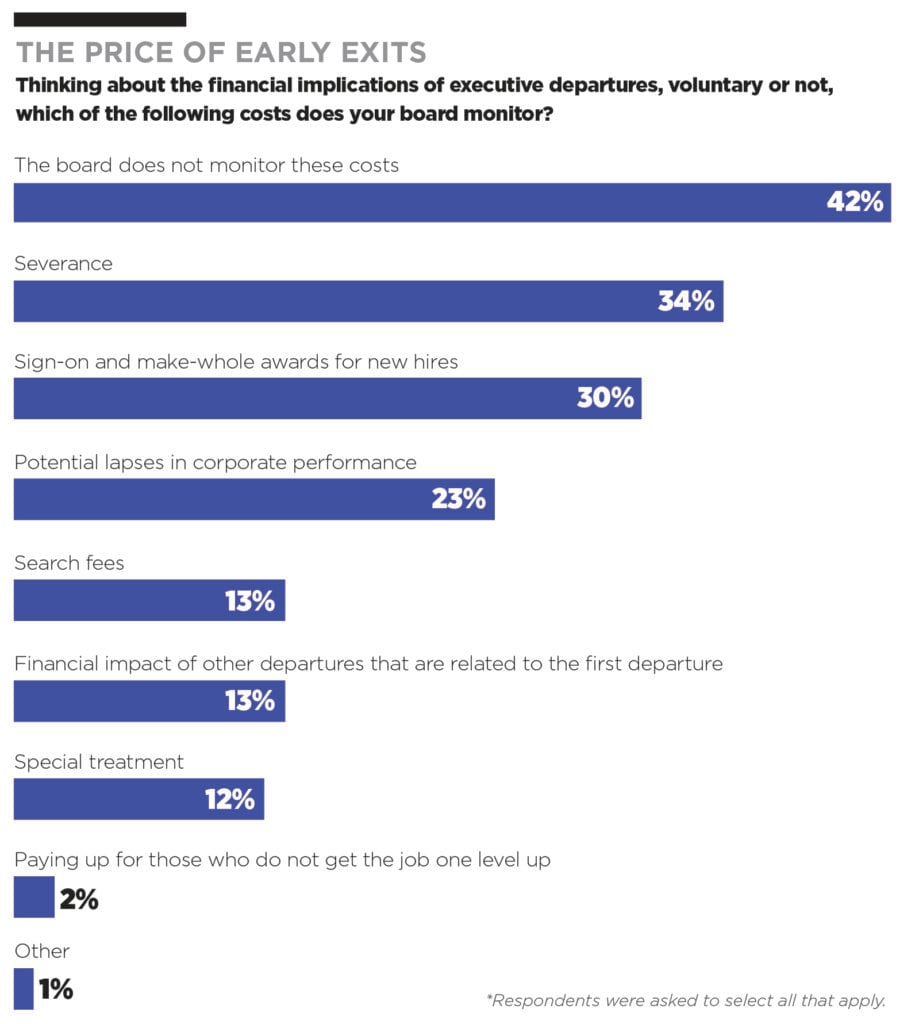

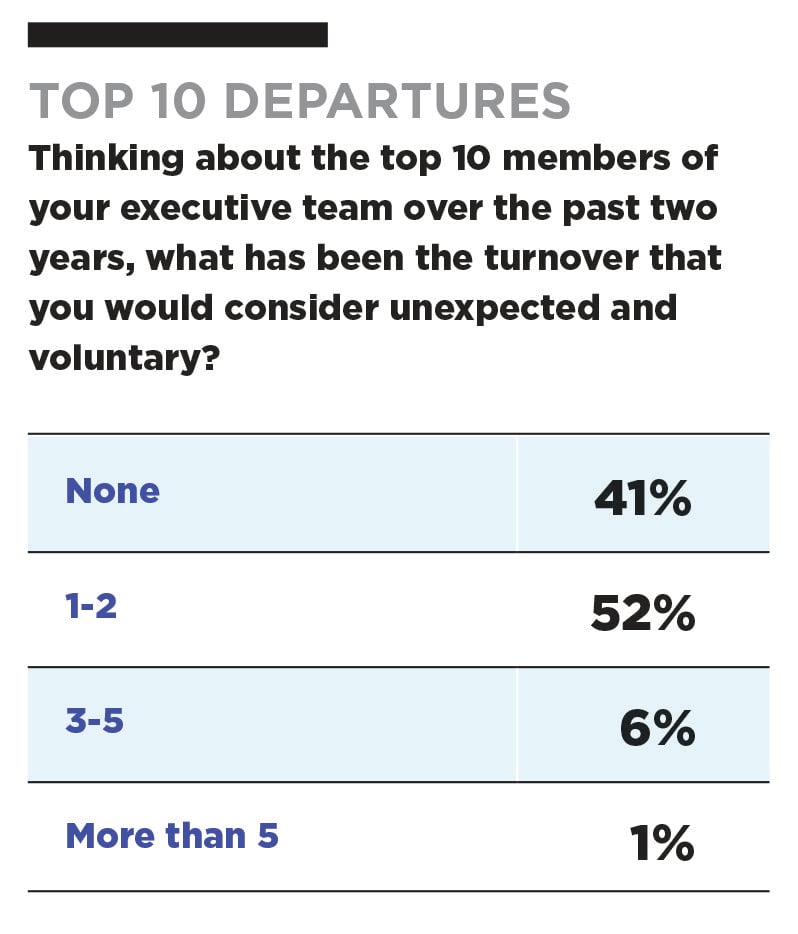

Lack of clarity regarding CEO turnover risk can be costly, noted Robin Ferracone, founder and CEO of Fariant Advisors and chairman of the Woodlands Financial Group's compensation committee. A leader's sudden departure can cause collateral damage within the company. This is what Fellacon calls the “rip-over effect.” “A sudden departure can lead to a wave of collateral impact, such as the departure of other C-Sweet executives, creating instability beyond the initial vacancies,” explains Ferracon. “This ripple effect extends to candidates for succession, especially when internal candidates are passed on for external recruitment.”

If internal candidates were deemed unprepared to step up, the company won off guard with a sudden vacancy. However, external recruiting is generally much more costly than promoting internally, as external recruits are more likely to receive a one-time sign-on award as a guide, or because they are more likely to “all” executives when leaving uninvested fairness.

“Our research shows that CEOs employed outside are paid about 30% more on average than retired CEOs,” Ferracon said. “In comparison, internally promoted CEOs are usually paid 20% less than leaving CEOs.”

Ultimately, these costs should be compared to the company's strategic goals and performance expectations, as well as other important costs, such as loss of institutional knowledge, disruption in strategic initiatives, and many other costs associated with the adoption of and adoption of new leadership.

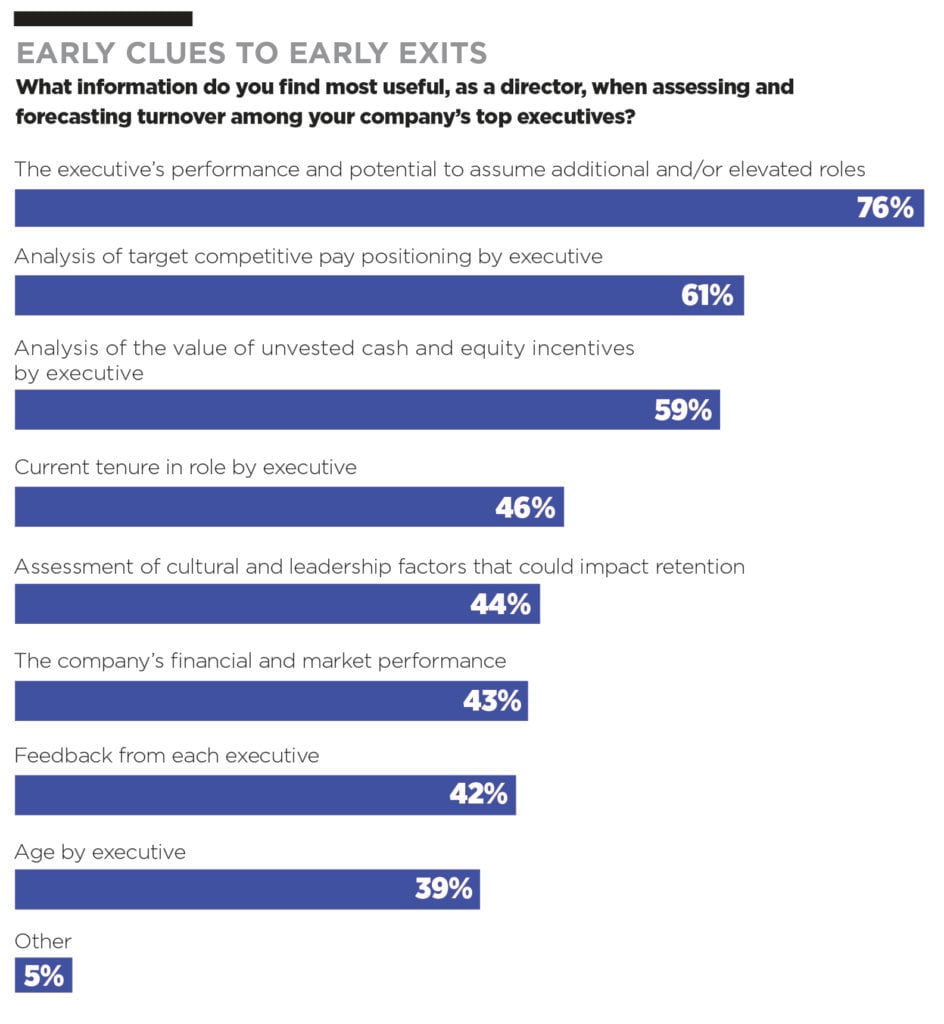

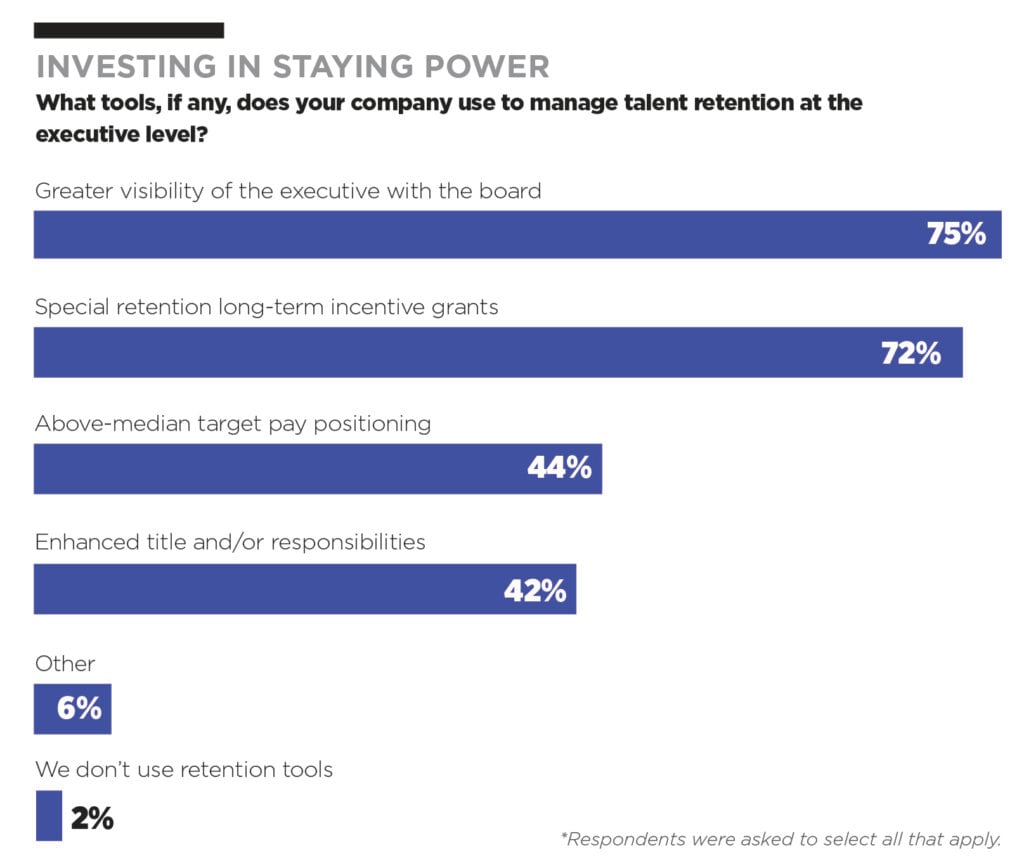

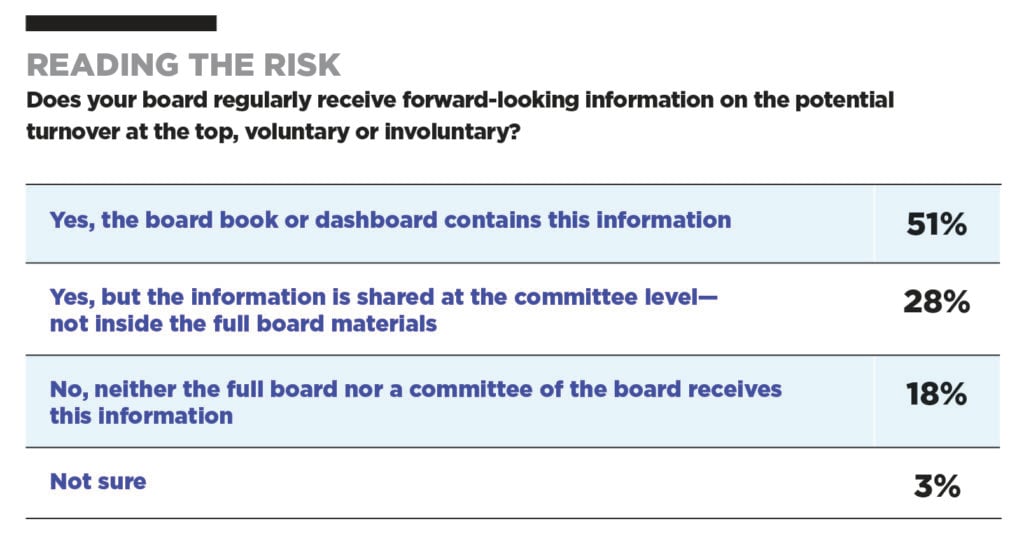

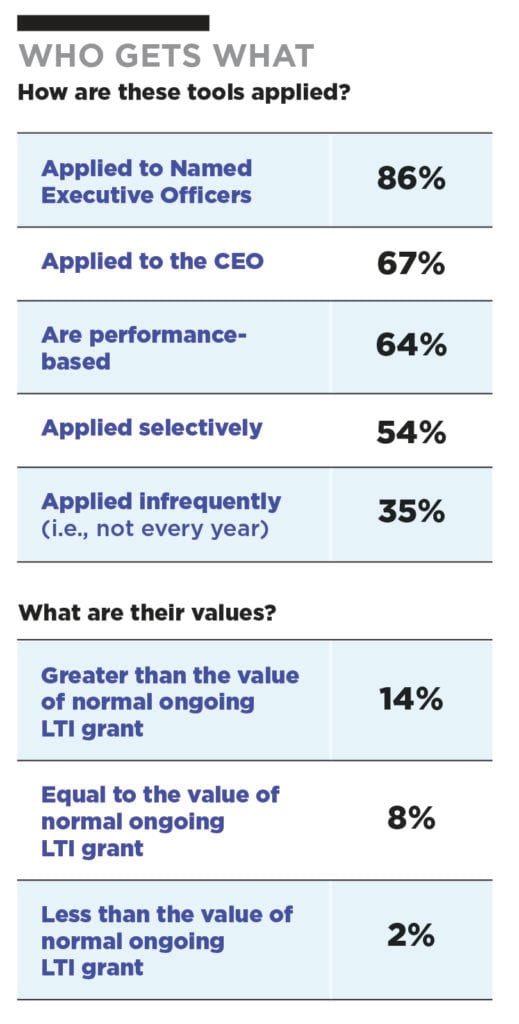

Among directors who say they use sales projections as part of their succession planning process, the most common metrics used to identify “flight risk” before leaving include executive performance, compensation for peers, and the value of long-term incentive planning. The focus on financial metrics will probably help explain why 72% say they use “special long-term retention incentive grants” as a tool for key executive retention strategies.

Avedon agrees that a proper pay package is the board's first line of defense. “I believe that the people most important to the future should not be paid in the market. If they are that important, they should outperform the market, especially in short-term and long-term incentives.

Although 44% of the boards surveyed agree that pay positioning on medians is a valuable tool to maintain top performers, the results suggest that other factors are important retention factors for today's market managers. “Money is important, of course,” Tehada says. “They want to be rewarded. They often have wealth creation goals for their families. They have short-term and long-term financial goals that they want to strike.”

But the overall culture, mission and purpose of the business also plays a key role, she adds. “Do you have bonds with your team, your peers, your executive team, and your organization?” she says. “What do you want to be with every leader you interviewed when you grow up? And it's really interesting to see how they answer that question. Understanding motivations, goals and interests helps you understand the type of runway and the opportunities that may be with each individual.”

One of the most important things a board can do when faced with the risk of losing an important executive is having a conversation, Sulzberger agrees. “These are important roles and if you think this person is at risk of flying, it guarantees a thoughtful conversation about all the reasons… My bias is very well aware of the individual situation. It's an important part of our job to have a clear understanding of what is going on with regard to important people,” she said.

But at the end of the day, you should not aim to be a CEO who never leaves. “My goal is not to keep someone forever,” Tehada says. “My goal is to have the right leaders in the right mission and the right moment, and that mindset has allowed me to identify great leaders about what I need in the next two to three years.