One of the compensation committee's primary responsibilities is to set corporate performance goals that form the basis of executive incentive plans for annual and long-term performance. Since executive remuneration is largely variable and linked to company performance, it is fundamentally important to set performance goals that are challenging and motivating, yet achievable.

When setting incentive targets, compensation committees typically establish performance expectations and associated payout outcomes. This is called the performance dividend slope, and it's what we'll focus on in this installment of our Executive Compensation Essentials series. The slope is centered around the desired performance goal, with minimum (threshold) and maximum performance goals on either side of the goal. Most commonly, there are no payouts below the minimum target, and payments are capped at the maximum target. Ideally, the slope of earnings and dividends is structured such that in most years, a company's year-end earnings are above the minimum and below the maximum at some point along the slope.

The question is not whether to link pay to performance, but how. sharply Compensation should change as performance changes. Consistently paying less than the minimum amount or the maximum amount may reduce the motivational impact of the program. Thoughtful slope design balances motivation and risk, strengthens accountability, and ensures that incentive outcomes remain meaningful across a variety of business contexts.

Starting point: Setting goals

Aligning performance and pay slopes begins with setting performance goals, which are the levels at which 100% of management's target incentives are paid. Target performance targets are typically based on a company's operating plan, including an assessment of expected growth, expense management, and balance sheet discipline, and reflect what the company expects to achieve during the year.

Operating plans that inform target performance objectives are typically approved by the full board of directors after a detailed review of the company's projected performance for the year. Often, but not always, when companies provide such guidance, target performance objectives are tied to performance expectations communicated to shareholders. Target performance targets are typically set at least at the midpoint of shareholder guidance, and often toward the high end of that guidance. Goals Goals need to be somewhat unreasonable, but also achievable if the company follows through on its plans for the year.

Payout slope: setting minimum and maximum values

Once the target objectives are set, the compensation committee must define minimum and maximum targets and review and approve a proposed performance pay slope built around the target performance objective. Market practices vary, but executives typically earn 25 to 50 percent of their target incentives for poor performance and up to 150 to 200 percent. So the incentives are: As the level of performance increases, management can earn higher levels of compensation. Consistent with market practice and good risk mitigation governance, management incentives are almost always capped.

There are two important related considerations when setting the performance pay slope. (1) how steep the slope is, and (2) how wide the range of performance around the goal is. Three important considerations when making these decisions are:

- Impact of metric type: In general, the more predictable the performance outcome, the steeper and narrower the slope. The steeper and narrower the slope, the greater the sensitivity to pay and performance. This means that it is more difficult to deviate from the expected outcome due to the higher level of predictability associated with the target goal. In contrast, less predictable outcomes often involve flatter and broader slopes to accommodate the potential for greater variability in outcomes. The potential for variation in results is often related to the performance metrics used. Generally, the higher up the income statement you are, the narrower the range of performance around the target.

| performance indicators | explanation | Range example |

| top line | The range of performance results is narrow compared to other metrics. | 95-105% of goal |

| conclusion | Because profit-based metrics start with revenue and are then adjusted for expenses and non-operating items, results are likely to vary and typically have a broader target range. | 85-115% of goal |

| cash flow | Because cash flow calculations start with income and are then further adjusted, there is often a wider range of performance around the target than would be seen with a profit target. | 80-120% of goal |

- Goal setting guidelines: When setting minimum and maximum performance goals, it may be helpful to consider the associated expected probabilities of achieving those outcomes. As a rule of thumb, minimum performance goals should be achieved 80 to 90 percent of the time (i.e., 8 to 9 years out of 10), while maximum performance goals should only be achieved 10 to 20 percent of the time (i.e., 1 to 2 years out of 10). A useful insight when considering probability is to look at a company's past performance over the past 10 years and determine the percentage of time the company was at thresholds, targets, and maximum performance levels.

- Market practices: Also consider the alignment of performance slopes among a company's peers or industry peers. Looking at trends among your industry peers with similar maturity, size, and industry focus can provide useful context. For public companies, this information is often disclosed in shareholder proxy statements.

Slope calibration variations

Symmetrical performance ranges are often observed. For example, the minimum performance goal is set to 90 percent of the target goal, the maximum performance goal is set to 110 percent, and payments for results between these points are linearly interpolated, but the slope of performance and pay may vary from the norm.

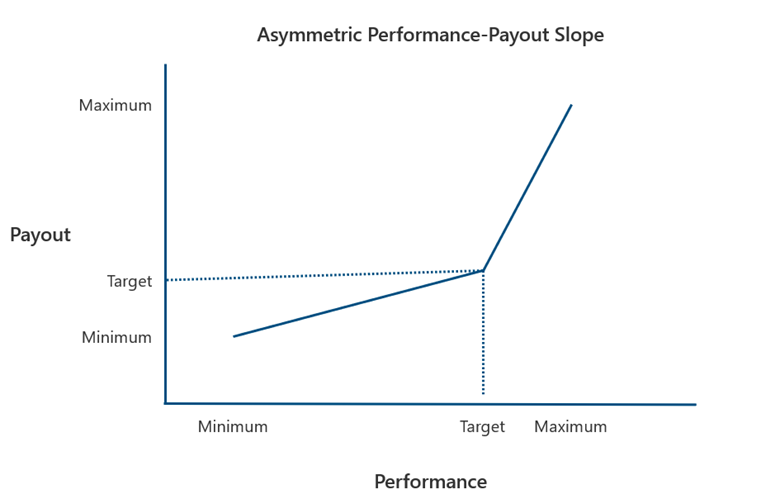

- Asymmetrical slope: Depending on the stringency of the target objectives involved, an asymmetric performance pay slope on each side of the target may be desirable. For example, if a goal goal is considered to be a stretch goal, given the difficult nature of the goal, it may be appropriate to consider a flatter, longer slope below the goal to protect the downside, and a steeper, shorter slope than the goal to provide a higher payout for each increase in performance above the goal.

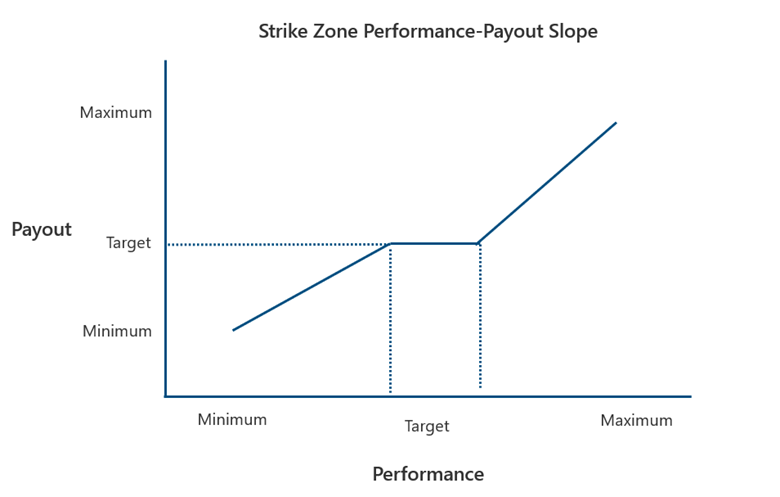

- Strike zone: If you expect the dispersion of results around the target to be higher than usual, you may want to consider setting a flat slope around the target (for example, 98 to 102 percent of the target will yield a 100 percent payout).

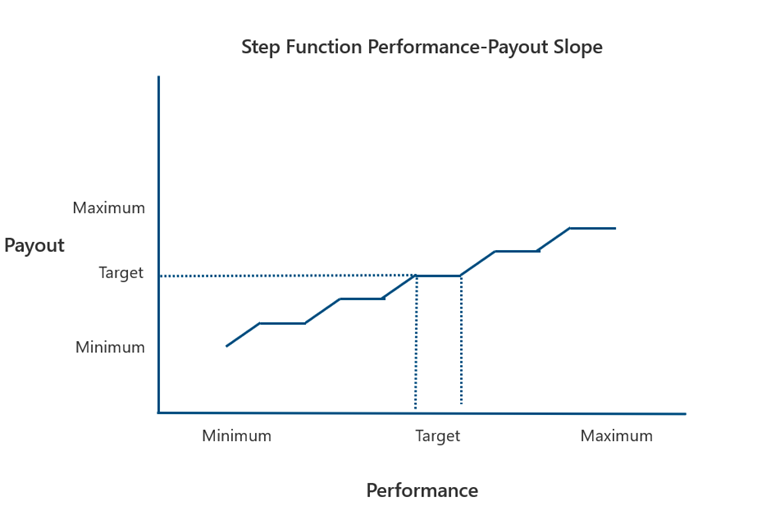

- Step function: Similar to the strike zone concept, a step-function slope creates a mini-strike zone at each point along the slope. Step functions have less pay-for-performance sensitivity than linear slopes, but may be appropriate when outcomes along the slope are less predictable.

The performance and payout slope is worth your time.

Effectively designed performance and reward slopes are central to aligning executive incentives with sustainable value creation. By carefully aligning goals and performance ranges based on predictability of performance, past results, and market practices, compensation committees can strengthen motivation, manage risk, and improve the alignment of compensation to performance, ensuring that incentive plans remain credible and persuasive over time.