A critical benefit of being a private company is often cited as freedom from quarterly financial reporting and onerous reporting obligations. Without regulatory reporting requirements and public market oversight, private company leaders say they have more freedom to focus on long-term strategy.

But new survey data reveals an interesting pattern. Despite that freedom, many private companies have governance approaches that are very similar to publicly traded companies, raising questions about how ownership structure impacts actual strategic planning.

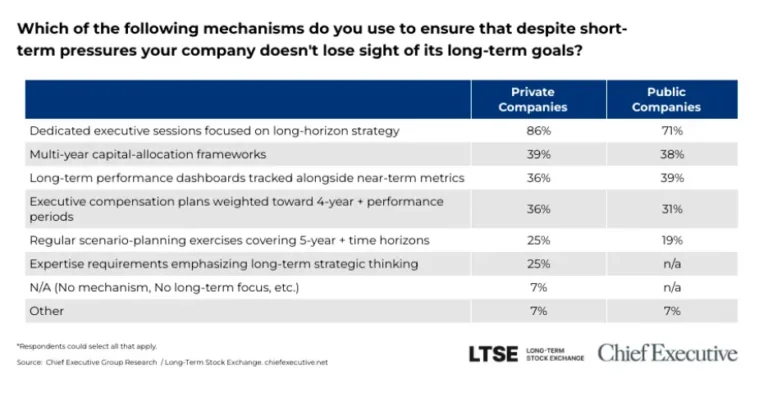

A new study conducted by Chief Executive Group Research in partnership with the Long Term Stock Exchange finds that private company leaders value independence from short-term pressures, but relatively few companies employ the mechanisms typically associated with disciplined long-term oversight. Fewer than 4 in 10 private companies report using multi-year capital allocation frameworks, long-term performance dashboards, or incentive structures tied to multi-year results.

When asked how they keep short-term pressures from overshadowing long-term goals, 86% of private company respondents said they hold dedicated board meetings focused on long-term strategy, compared to 71% of public company leaders. However, beyond that, the numbers converge.

Perhaps even more noteworthy, private company leaders report spending just 25 percent of executive board time discussing long-term alignment. This is the same as other publicly traded companies in the same industry.

“This research highlights that long-term thinking is more about intentional design than ownership structure,” said Maris Beams, CEO of Long Term Stock Exchange Group, a partner in the study. “Private companies have flexibility in how they set accountability and track progress, and the most effective leaders use that flexibility to align governance, strategy, and incentives around superior long-term value creation.”

The findings come at a time when interest in going private remains high. Listed companies are increasingly citing the cost of regulatory compliance and the burden of quarterly reporting as reasons for exiting public markets. Several survey respondents expressed similar sentiments.

The CEO of one of the private companies surveyed said, “The high cost of regulatory compliance is a major factor in encouraging listed companies to go private.''

“It makes it easier to run the business,” added another person, stressing the benefits of going private. “The number of reports is decreasing and it's giving me a headache.”

This reduced administrative burden is a clear advantage of private ownership. However, the survey data suggests that there may be trade-offs in how companies build accountability for long-term goals. Nithya Das, Chief Legal Officer and General Manager of the Governance Business Unit at Diligent, works closely with private organizations on governance structures. She points to governance as a key factor in whether a company can translate its long-term aspirations into sustainable growth.

“Too many CEOs and private companies make the mistake of believing they don't need to invest in governance until they are close to an IPO or a larger growth milestone,” Das says. “But in my experience, private companies that put these public company governance mechanisms in place early in their lifecycles are the ones that are able to control their own destiny.”

Private equity and venture capital-backed companies often introduce tight oversight structures early on, with compressed growth schedules and clear performance expectations. In contrast, a family-owned or employee-owned business may allow for more flexibility in terms of goals and schedules. Das says that flexibility can be costly if it leads to undisciplined decision-making.

“I think if companies can start to make the governance of their decisions more efficient, they will actually start to execute better,” she says. “They start running faster and posting results faster.”

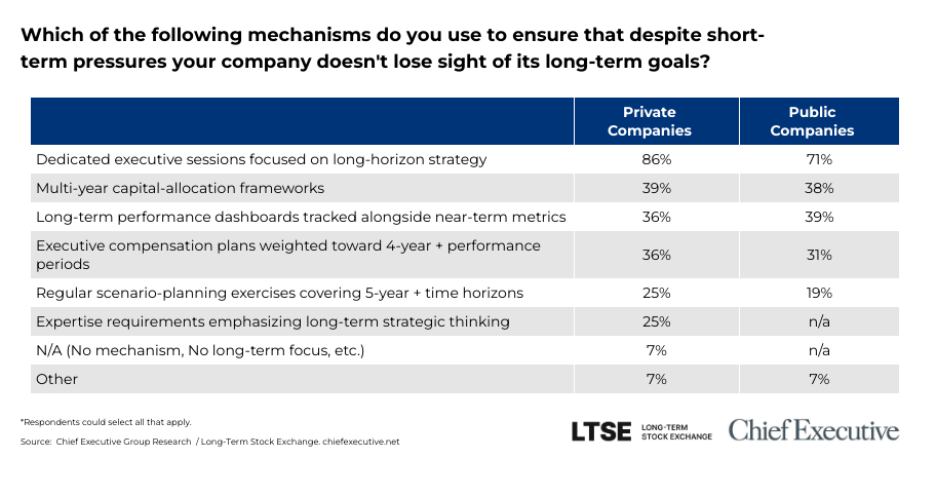

Without a structured process, companies risk becoming engulfed by immediate demands. Das describes this as a “hamster wheel,” where a leader's attention is absorbed by the next urgent task rather than long-term priorities. Survey data reflects that tension. On average, private companies' long-term strategic growth plans extend only five years into the future. Nearly a third of respondents plan three to four years ahead, but only 18% are looking more than 10 years ahead.

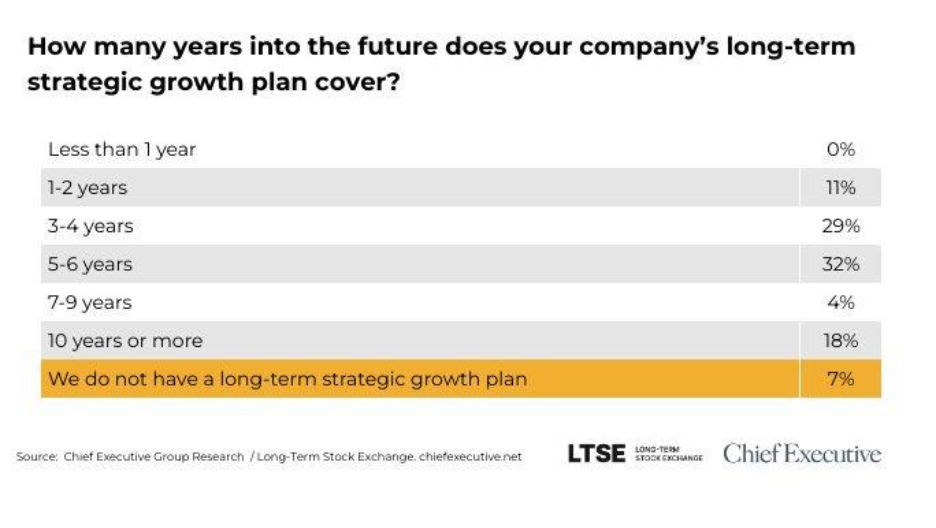

The relatively short planning period may help explain another finding. Private companies are not required to report their results quarterly, but many still choose to do so. Almost half of respondents said they review financial and operational performance against long-term strategic plans on a quarterly basis. A further 18% conduct reviews every six months, while almost a third only conduct reviews once a year.

“In conversations with CEOs of late-stage private companies, we found that there is wide variation in how long-term strategy is actually managed.As companies grow, complexity increases, and informal decision-making often gives way to more structured reviews and governance,” says Shahnawaz Malik, Head of Private Markets at LTSE. “The challenge is not to avoid short-term pressures completely, but to put mechanisms in place that help leadership stay aligned with long-term goals as the business scales.”

Michael Carragher, CEO and chairman of VHB, a civil engineering company that has been in business for more than 50 years, places particular emphasis on quarterly accountability. He introduced quarterly board reports that track both current performance and progress toward multi-year goals.

“What we've really tried to do is identify the broad arcs and areas of impact and progress that we want to make, and not look four, five, six years down the line and prescribe in too much detail what those are,” Carragher says. “But whatever we do this year or the next two or three years, make sure that we're in a better position to get through the five or six year period and reach our goals.”

At VHB, long-term expansion goals, such as entering new geographic markets over five years, are broken down into intermediate steps and reviewed quarterly. “As long as we're moving in that direction and meeting our annual operating expectations, making sure everyone understands that these are the four or five big goals that we're trying to achieve in five years keeps everyone moving forward,” Carragher says.

That discipline, he points out, depends on having a clear picture of future success. Without it, decisions will naturally lean toward those that are immediately efficient or profitable. “We have to internalize the reaction and remind everyone of the long-term and connect the decisions we are making, even if they are short-term, to how it impacts or undermines the decision-making matrix and how we get to where we want to go,” he says.

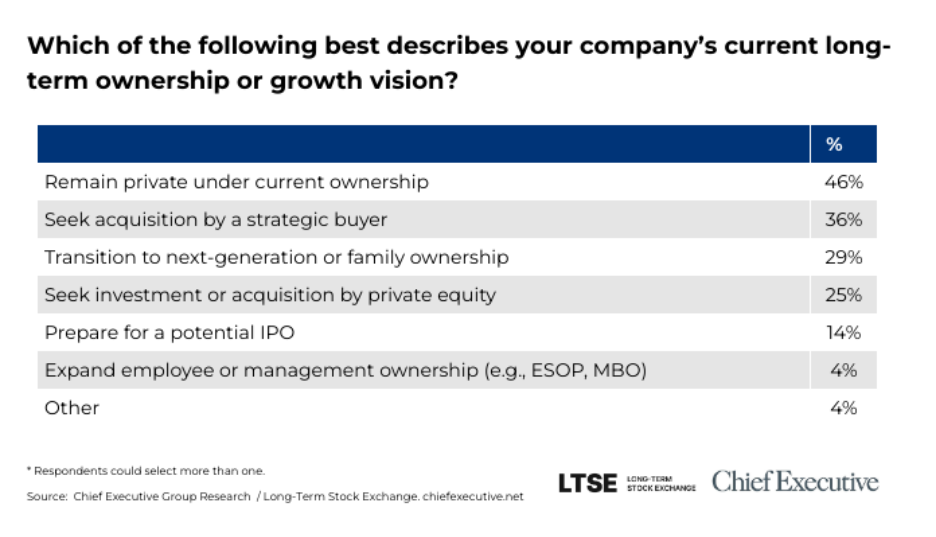

This research suggests that clarity on long-term direction is particularly important given the range of end states that private companies envision. Almost half of respondents expect the company to remain private under current ownership, while more than a third foresee a strategic acquisition. Some are preparing for private equity investment, next-generation ownership, or even a potential IPO.

Taken together, these findings highlight a picture of private companies that value long-term thinking but rely on familiar structures to achieve it. Even without quarterly earnings pressures, many companies continue to organize strategy, reporting, and accountability to the same rhythms as publicly traded companies, raising the question whether the freedom of private ownership lies not in abandoning those mechanisms, but in how deliberately they are used.