Published as part of the ECB Economic Bulletin, Issue 6 of 2019.

Household income and wealth inequality has become more important in explaining the macroeconomy. Since the financial crisis, there has been increasing recognition that heterogeneity among households and firms is key to understanding business cycle fluctuations (through balance sheets, credit constraints, etc.).[1] At the same time, public interest in the distributional aspects of economic policy continues to grow. Furthermore, the increasing availability of microdata makes it possible to document relevant microeconomic stylized facts. In this vein, this box sheds light on the relationship between business cycle fluctuations and changes in income at the individual worker level in the euro area.

There is evidence that household income risk changes over the business cycle and has an unequal impact on workers. Individual income risk may be considered the most direct type of household income risk, prior to insurance through social transfers or pooling of household resources. Based on this, Guvenen et al. We document variation in individual income risk using a large administrative microdataset from the United States.[2] They find that the skewness of income changes is strongly cyclical. This means that during a recession, your income is less likely to increase significantly, but it is more likely that your income will decrease significantly. Moreover, they find that aggregate shocks do not affect workers with different characteristics in the same way. That is, the incomes of some workers (e.g., young people, low-wage workers) are systematically more susceptible to business cycles than others. This is quite different from the purely random income shocks that are primarily used when modeling household income risk.

Household income risk is important for the transmission of macroeconomic shocks and the transmission of economic policy. Several authors have found that the dynamics of household income risk give rise to cyclical precautionary saving motives that significantly increase the sensitivity of consumption to changes in aggregate income.[3] There is also evidence that households with higher income risk have a larger marginal propensity to consume outside of disposable income (MPC), making aggregate consumption more susceptible to business cycles.[4] To the extent that household incomes with higher MPC benefit more from macroeconomic stabilization policies, the diversification of household income risks also amplifies the effects of fiscal and monetary policies.[5]

Changes in income risk in the euro area can be studied using survey data on income. Until recently, there has been no systematic analysis of trends in individual earnings risk in the euro area over time and across individuals, due to limited data availability. To address this, this box uses longitudinal data on individual income levels observed over a four-year period provided by the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC). The analysis focuses on the four largest countries in the euro area. This allows for a deeper understanding of the stylized microeconomic facts of the euro area as a whole, taking advantage of national differences in economic structure and recent macroeconomic developments.[6]

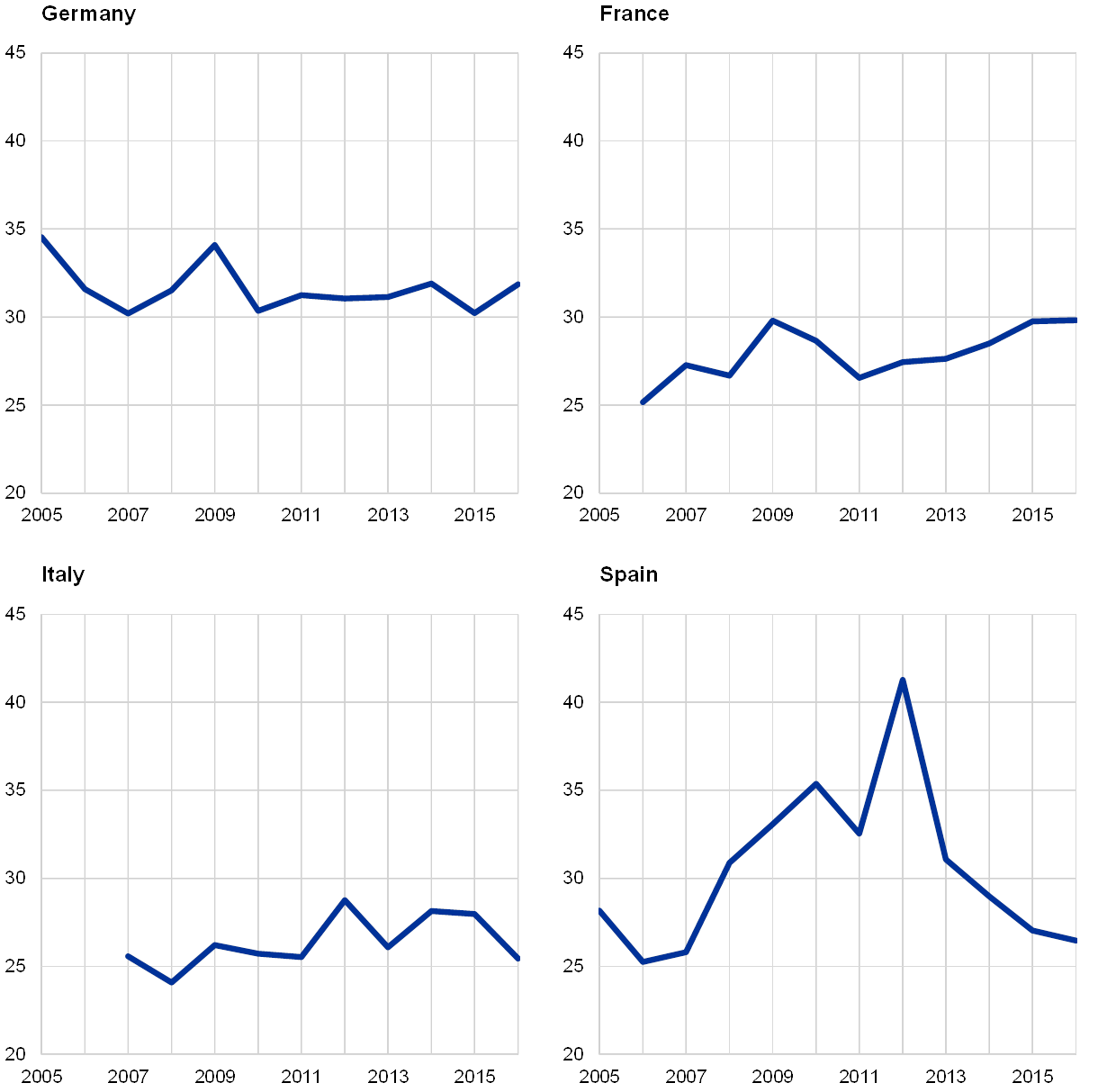

Chart A

Downside risk of labor income

(Percentage of individuals experiencing a decrease in labor income)

Source: Eurostat, DIW Berlin, ECB calculations.

Note: Proportion of individuals aged 25-65 experiencing a decrease in labor income (based on the EU-SILC variable PY010G for total employee cash income in the longitudinal data file. The EU-SILC longitudinal data file clone of GSOEP is Germany).

Downside risks to income are cyclical in the euro area, but vary widely across countries. Graph A shows the change in the proportion of workers experiencing a decrease in labor income (i.e. income risk realization) compared to the previous year.[7] Because the number of workers who are unemployed increases during a recession, the proportion of workers who experience a decrease in income increases during a recession, and vice versa. This was clearly seen in 2008 and 2009 during the financial crisis, but even more so in Spain in 2011 and 2012 during the sovereign debt crisis. In Spain, the large fluctuations in the unemployment rate are also reflected in the large fluctuations in the proportion of workers experiencing a reduction in their labor income. This is less common in Germany, France, and Italy, where labor markets are known to be less fluid.

Chart B

Changes in labor income after a significant decrease in income

(Normalize first year income to 1)

Source: Eurostat, DIW Berlin, ECB calculations.

Note: Trends in regularized labor income for men aged 26–50 who experienced a significant income decline (defined as a 15% or more decline in income) in 2007 or 2013 (income is the EU-SILC variable for total employees) Based on PY010G) Cash income in longitudinal data file. For Germany, GSOEP's EU-SILC longitudinal data file clone is used.

This suggests that the downside risk to income is persistent and has a significant impact on lifetime income. Graph B shows that after a person's labor income declines significantly, their income in the following two years also tends to decline significantly. This suggests that real risks of lower incomes persist, and that job losses can have a significant impact on individuals' lifetime labor incomes and, therefore, on personal consumption.[8] Moreover, its persistence also appears to depend on the state of the business cycle, with the decline in income since the start of the current economic expansion in 2013 not as persistent as that seen at the beginning of the financial crisis. Apparently not. Although there are large differences across countries in the variation in the proportion of workers experiencing a decline in labor income, the extent to which it persists appears to be fairly similar.

Chart C

Beta for workers across the income distribution

(Income elasticity with respect to GDP growth rate)

Source: Eurostat, DIW Berlin, ECB calculations.

Note: Estimated labor income elasticities for aggregating GDP growth across the household income distribution (to avoid spurious correlation between exposure and classification, individuals are divided into income quintiles based on their previous two years of household income). Household income is based on EU) SILC variable HY020 Total disposable household income in the longitudinal data file. GSOEP's EU-SILC longitudinal data file clone is used for Germany. Gray areas represent 95% confidence limits.

Income risks in the euro area vary for individual households. Graph C reports the “worker beta” documented in Guvenen et al. For the United States.[9] Labor beta measures the elasticity of labor income to changes in aggregate GDP growth. Across the income distribution, the sensitivity of labor income to changes in GDP growth is significantly higher for workers in low-income households. This pattern is particularly visible in Germany, France, and Italy. In Spain, the sensitivity of labor income to GDP growth for low-income households is comparable to that of workers in other countries, but does not decline significantly as household incomes rise. This may reflect that unemployment rates in Spain are generally more volatile and affect workers more evenly across the income distribution.[10] However, identifying a structural explanation for this finding is beyond the scope of this box.

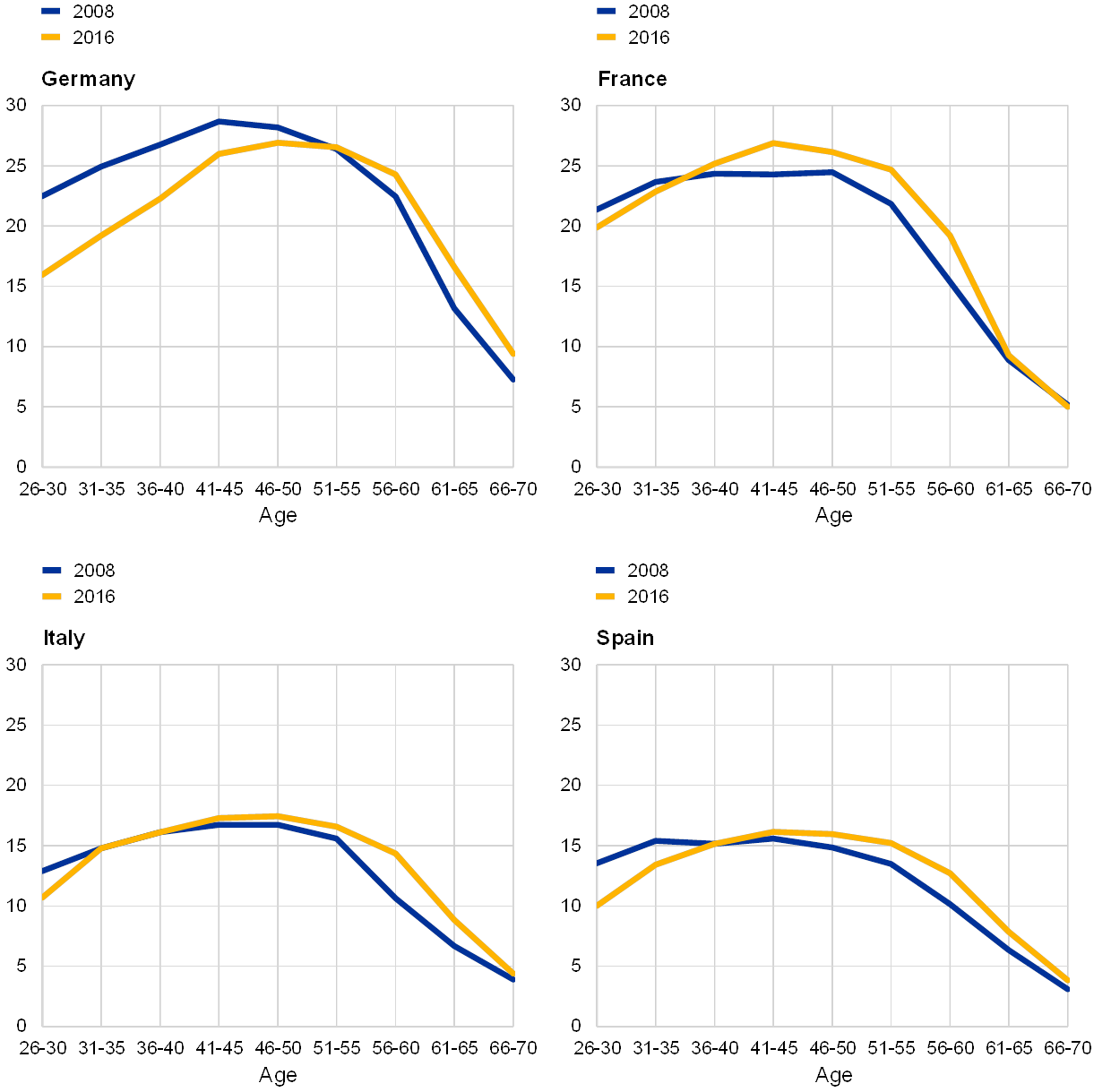

Chart D

Labor income across the age distribution

(several thousand euros per year)

Source: Eurostat, DIW Berlin, ECB calculations.

Note: Estimated labor income for individuals aged 26-70 (5-year groups) in constant euro in 2015 (based on the EU-SILC variable PY010G for total employee cash income in the longitudinal data file. EU-SILC longitudinal data file) GSOEP clone is used in Germany).

The distribution of income risk also shows who primarily bears the costs of business cycle fluctuations. Macroeconomics has long debated the welfare costs of the business cycle. Using a typical agent model, Lucas argued that the welfare costs of recessions are fairly small.[11] This means that the basis for adopting macroeconomic policies aimed at stabilizing the business cycle is quite weak. Research since Lucas has shown that understanding both the distribution of income and consumption losses and their persistence is key to assessing how harmful economic downturns are.[12] In this context, Exhibit D shows the distribution of real labor income by age group in 2008 and 2016. This suggests that younger workers' incomes have not increased as much as older workers' incomes since the financial crisis. In Germany and Spain, young workers' real earnings in 2016 were even lower than in 2008. Given the heterogeneity across individuals, cyclical welfare costs are likely to be significant in the euro area.

Household income risk behaves similarly in the euro area as in other countries, and this insight is useful in assessing the current economic outlook. Overall, this analysis shows that, as in the United States, (i) individual earnings risk is strongly related to labor market performance, and (ii) some groups of workers are much more at risk during economic downturns. It suggests that it will get bigger. others. This is important for understanding how economic policy is transmitted and macroeconomic shocks are amplified. The continued resilience of the labor market (see Section 3) in the wake of the significant external shock that recently hit the euro area economy suggests that household income risks have so far amplified the macroeconomic impact of this shock. It might help explain why there isn't.