From theory to practice

In 1962, economist Paul Samuelson showed that time dispersion is a mathematical fallacy when using standard economic assumptions. In other words, the idea that investors should hold relatively safe assets for short-term goals and finance long-term goals with riskier assets is a fallacy. According to Samuelson, if you loved stocks for 40 years, you'll probably love stocks the same way for one month.

Future researchers have circumvented Samuelson's findings, but have not disproved them. However, his discoveries remain ignored. Morningstar, like other investment websites, regularly publishes articles based on time diversification. Investment professionals do the same when creating their portfolios. For example, all funds with a 2050 target date own more stocks than funds with a 2025 target date.

I'm not writing this to challenge common practice. I agree with that. (I'll explain why next week.) My point is to acknowledge the existence of Samuelson's argument. In the end, it's not convincing. However, if that is what convinces you, then what is presented in this article is irrelevant. Consider yourself forewarned.

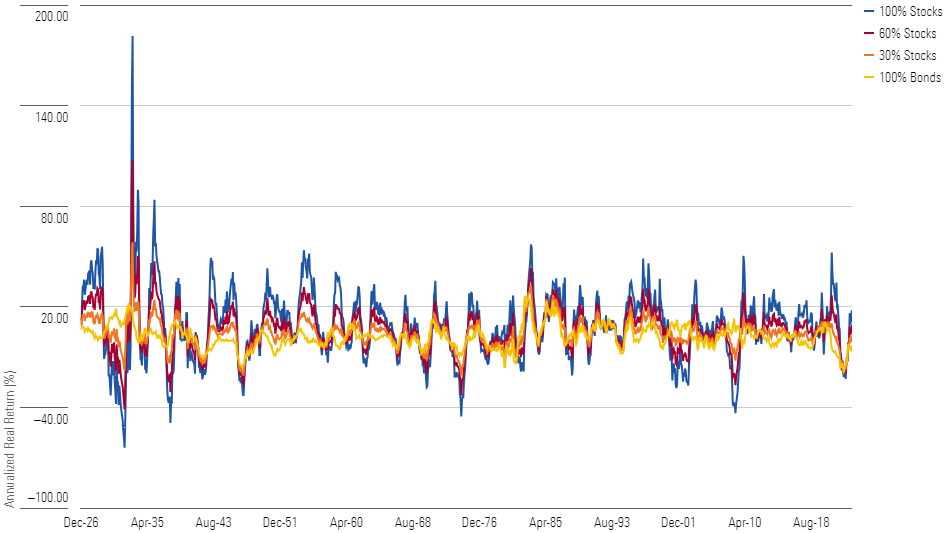

Duration: 1 year

This column contains four charts. Each represents the same information over time periods of different lengths. These show the after-inflation returns of his four portfolios since January 1926. 1) 100% US large company stocks, 2) 60% stocks, 40% US medium-term government bonds, 3) 30% stocks, 70% bonds, 4) 100% corporate bonds. The first photo shows his results for one year and looks familiar.

However, I had to revisit the initial blue line. Indeed, for the 12 months from July 1932 to June 1933, stocks made him 180% of his return, after inflation. Sadly, the stock lost money in five of his next eight calendar years.

Here are some summary statistics. This table shows how often the 100% stock portfolio outperforms the other three portfolios. It also shows how often each investment suffered his double-digit losses (returns are in real terms).

1 year overview

Surprisingly, at least to me, the stock had essentially the same win rate against each of the three alternative portfolios. I thought Bond's performance was the best. However, the double-digit loss percentage matched my expectations. The more bonds you have in your portfolio, the more likely you are to avoid that fate.

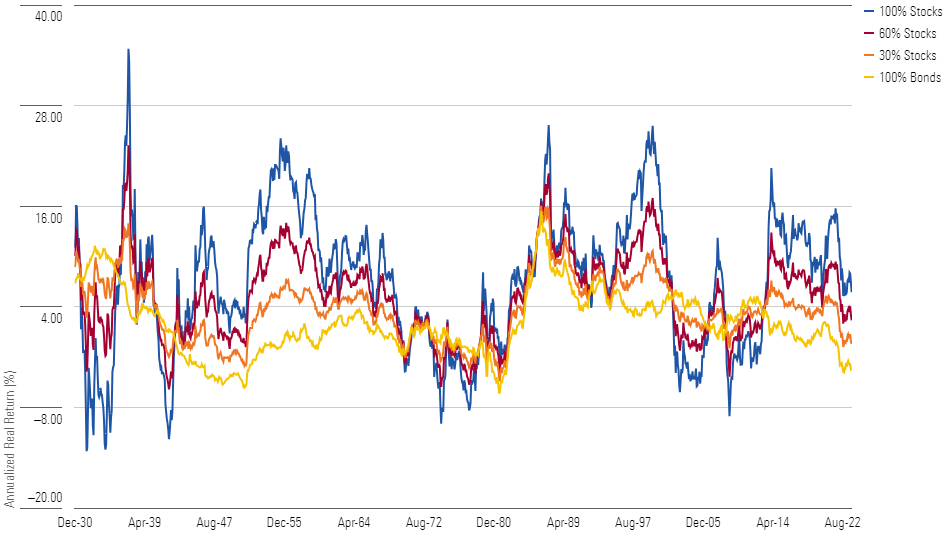

Target period: 5 years

This photo looks different. The blue line representing a 100% stock portfolio continually jumped up and down on his 1-year chart, never consistently leading or trailing the other lines, but how many on his 5-year chart. You can see the pattern. Not only did the blue line spend significantly more time than other lines during the Great Depression, it also spent longer periods ahead of other lines in the 1950s, late 1990s, and 2010s.

But overall, the results are similar to the one-year results. The win rate of the 100% stock portfolio increased slightly, but not by much. Again, that portfolio resulted in one double-digit loss in his six trials. (This calculation, like the 10-period and 20-period calculations, is cumulative; that is, if you put it in the loss column, the return for the entire period was less than -10%, and the return was less than -10%.) (Annualized.)

5 year overview

The only surprise and disappointment was the 100% bond portfolio, which posted double-digit losses 13% of the time, compared to just 3% in a single year. This is bad news for bond investors because bond market problems tend to occur in clusters rather than randomly.

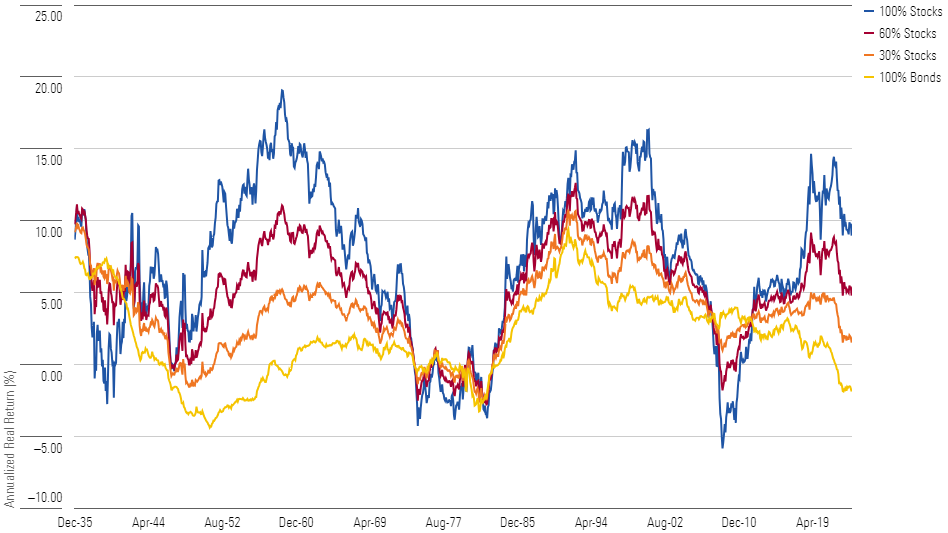

Target period: 10 years

If we widen our horizon to 10 years, the picture for stocks becomes noticeably brighter. The blue line has been above the other lines for a long time, including a 25-year extension. On the contrary, during his three eras, which occurred decades apart, he only follows the crowd for a short period of time.

Summary statistics for 100% stock portfolios have also made progress, but improvements are still gradual. The portfolio win rate increases to approximately 80%. While impressive, this means that for one out of every five years of the decade, investors would have been better off mixing in some bonds or (somewhat less often) skipping stocks altogether. It is shown that.

10 year overview

Not that the latter choice was wise. Given a 10-year period, bonds will most likely replace stocks as a portfolio, losing at least 10% of their value. 100% stock portfolios experienced the largest losses during the worst times, while 100% fixed income portfolios experienced even more double-digit declines.

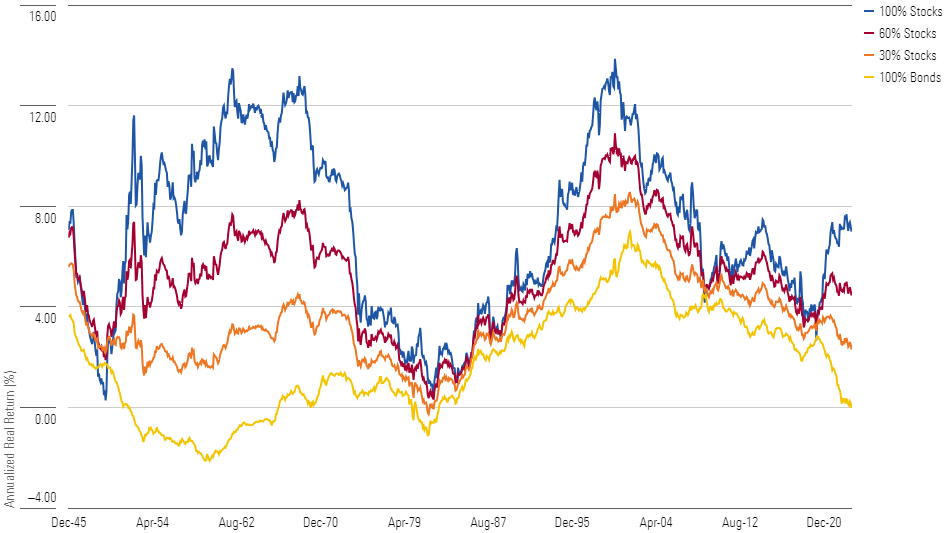

Target period: 20 years

The contest will end if the period is extended to 20 years. Since very early observations incorporating the Great Depression, 100% stock portfolios have almost always outperformed alternative portfolios, often by a large margin. Even a quick look at the chart leads to the conclusion that the blue line is significantly better.

Summary statistics confirm the impression. (Not that they can deny it; this picture certainly tells the whole story.) Diluting a stock portfolio with bonds has a 93% chance of increasing total return for moderate bond contributions. 97% of the time, the total return will decrease if the position is large. , and a whopping 99% of the time the bond replaces the entire position.

Overview of 20 years

In 2020, the risk assessment will be reversed. The real danger is in bonds, which routinely incur double-digit losses once inflation is taken into account. A safe path comes from stocks. Investing his 30% of the portfolio in stocks would eliminate cumulative losses of more than 10%, but in some cases the 30% stock portfolio reduced his purchasing power over 20 years. However, once stocks make up 60% or the entire portfolio, the losses disappear. In no rolling period over the past 20 years has a balanced portfolio or a 100% stock portfolio ever been in the red.they always got the least something.

The opinions expressed here are those of the author. Morningstar respects diversity of thought and publishes a wide range of viewpoints.