Business investment in the U.S. is on the rise. Since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was passed in late 2017, U.S. companies have been buying more machines, developing more software, and creating new intellectual property.

Some believe that the key to this growth in business investment is the fact that the law lowered the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, lowering the cost of capital which, at least in theory, could encourage business managers to invest more.

But our recent research suggests a simpler explanation: business investment is rising because domestic demand and sales are growing. We also find that rising market power (the ability of companies to set prices above their costs of production) blunts the impact of corporate tax cuts on business investment decisions.

Domestic demand and sales are increasing, leading to increased corporate investment.

Investment drivers

Sales growth and optimism about future sales prospects are central forces influencing companies to invest more.

For example, if a business owner expects sales to continue to be strong in the next quarter, they will likely invest more in the business and increase production.

Our research, published ahead of the latest U.S. economic assessment, finds that almost all of the growth in business investment since 2017 can be explained by the private sector's forecasts of future demand for products.

To measure expectations of future product demand, we used private sector forecasts of growth in U.S. domestic consumption and net exports (i.e., the noninvestment portion of output).

While future sales prospects play a key role in encouraging business owners to invest more, what motivates consumers to spend more?

Factors that boosted demand in 2018 included higher disposable income for households due to personal tax cuts in the Tax Act and increased government spending due to the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018. Other factors, such as lower capital costs due to lower business taxes, seem to explain little of the increase in investment.

Increasing corporate market power

So what explains the relatively muted investment response to the reduction in the effective corporate tax rate?

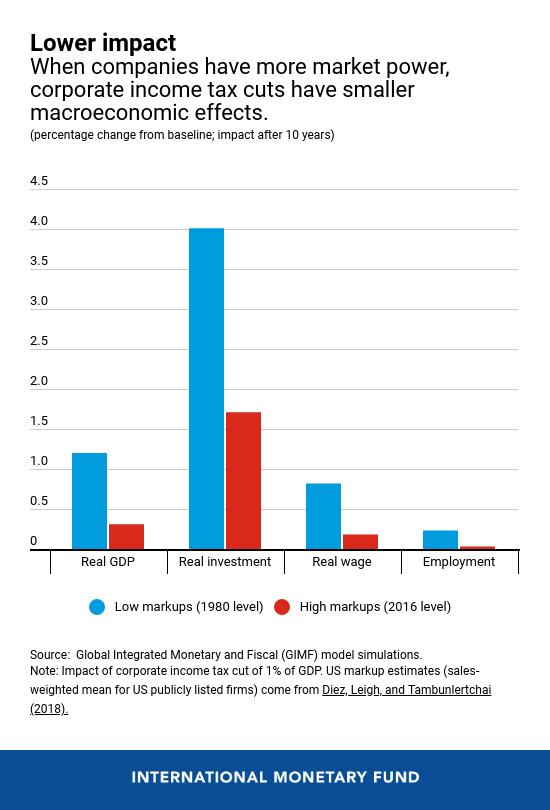

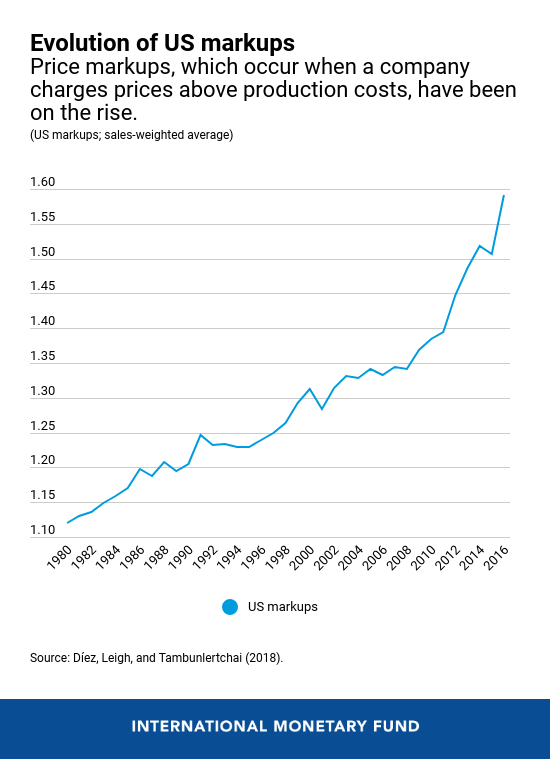

Our analysis suggests that the growing market power of large corporations over the past three decades may have made investment less sensitive to tax changes, a trend other studies have found is playing out across the economy, from airlines to pharmaceutical companies to tech companies.

As firms gain market power and their industries become concentrated, their profits increasingly take the form of monopoly rents that far exceed the normal profits that can be made in the face of increased competition.

In such an environment, a reduction in corporate tax rates should increase after-tax monopoly profits but produce smaller behavioral responses in firms' production and investment decisions.

Thus, as the graph shows, changes in the U.S. business environment would likely mean that tax cuts would have a smaller impact today than they have in past decades.

Investment decision

Firm-level data from 2018 also support the idea that rising market power is making companies less sensitive to tax changes. For publicly traded companies across industries in the United States:

Firms with higher markups (the difference between price and marginal cost) before the tax cut saw smaller increases in investment in 2018.

We believe other factors that have further dampened investment growth since 2017 include economic policy uncertainty amid rising trade-related tensions between the United States and other countries.

The bottom line is that strong demand since the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is the primary driver of corporate investment decisions, not the reduction in capital costs that comes from the corporate tax cuts themselves.

Moreover, the increase in corporate market power in recent decades appears to have weakened the effectiveness of corporate tax cuts as a tool to stimulate business investment.

Finally, policymakers can support further growth in business investment by reducing economic policy uncertainty, including by resolving trade-related tensions.