December 13, 2019

Increasing Business Cycles Synchronization: The Role of Global Value Chains, Market Power and Extensive Margin Adjustments

François de Soyres and Alexandre Gaillard1

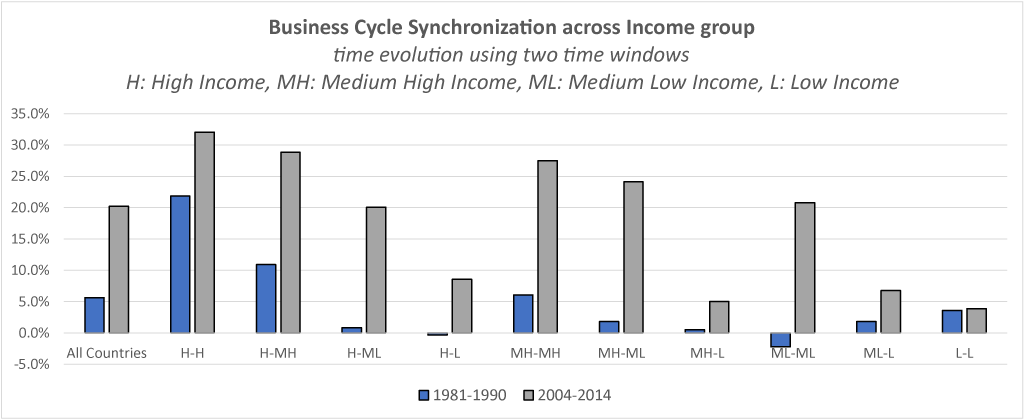

Over the past 30 years, international business cycle co-movements have increased markedly all over the world. In the 1980s, economic cycles in different countries were largely independent from one another, especially for middle- and low-income countries. But economic activity since the start of this century has since become much more correlated, especially for higher income countries (figure 1).

Figure 1: Countries’ economic activity is more synchronized than ever

This is an important phenomenon as the degree of synchronization of economic activity across countries can have implications for macroeconomic policies. For example, the extent to which the Euro Zone can be considered as an optimal currency area (and, therefore a common monetary policy could be optimal) largely depends on the synchrony of business cycles among the member countries. Moreover, greater correlation of economic activity among countries could signal higher interdependence and call for greater coordination of public policies as well.

How to interpret the increased business cycle synchronization over time? Have shocks become more correlated over time (Imbs 2004)? Or is it that shocks are propagated across countries due to a greater extent now (Frankel and Rose 1998)? In the latter case, are the increased spillovers of shocks mostly to trade linkages or financial linkages?

In this note, based on de Soyres and Gaillard (2019a, 2019b), we argue that the propagation of shocks across countries through trade linkages is large and propose the first model that accounts for such propagation with a magnitude in line with the data. The model relies on the combination of three key ingredients: (i) trade in intermediate inputs, (ii) price distortions and (iii) extensive margin adjustments. This has several implications for how you might interpret the increased synchronization, which are discussed below.

The Role of Global Value Chains

Using within country-pair variations over time and controlling for many observable and non-observable factors, our research shows that trade in intermediate inputs, linked to the development of Global Value Chains (GVCs), are strongly associated with the recent increase in business cycle synchronization. On the contrary, trade in final goods as well as financial linkages measured by either foreign direct investments or cross-country claims do not seem to have a large impact.

This finding implies that economic fates of countries participating in GVCs are tied to one another. Even if at the microeconomic level individual firms in different countries continue to compete, the aggregate health of an economy increasingly depends on the health of other economies supplying inputs or buying outputs.

The Trade Co-movement Puzzle

Following our previous insight about the specific role of GVCs, one might think that adding a fragmented production process across countries would help international macro models generate a strong link between trade and GDP co-movement – as observed in the data. However, things are not that simple, and several authors showed how the inclusion of GVCs into an otherwise standard model does not fundamentally change its propagation property: in those models, the association between GDP comovement and trade proximity is still too low compare to the data (Johnson (2014), Arkolakis and Ramanarayanan (2009)). This issue has been referred to as the “Trade Co-movement Puzzle”. Simply put, it refers to the inability of standard international business cycle models to quantitatively account for the observed positive correlation between international trade and GDP co-movements.

Our research shows that solving the puzzle requires introducing (at least) two other important elements: changes in aggregate profits (which means dropping the assumption of perfect competition), and fluctuations along the extensive margin. With these elements, we can account for the observed relationship between trade and GDP co-movements. We discuss in more detail these elements below.

The role of profits in GDP movements

An old insight must be summoned here. In perfectly competitive models, changes in real GDP can be decomposed into two parts: (i) changes in the supply of domestic production factors, or (ii) changes in productivity (defined as real GDP divided by production factors). The last term is also called the Solow Residual, and is sometimes considered as a measure of an economy’s aggregate technology. According to this logic, when a foreign shock hits, domestic real GDP reaction must come from either a change in domestic aggregate technology, or a change in the supply of domestic production factors. Holding technology constant, Kehoe and Ruhl (2008) then shows that foreign shocks do not have any impact on domestic productivity — in other words: if domestic GDP responds to a foreign shock, it is only through a change in factor supply. Hence, given the low elasticity of factor supply typically measured in the literature, it is not surprising that perfectly competitive models have a hard time generate a strong positive relationship between trade and GDP.2

One must bring another element in the picture: price distortions. Indeed, markups play an important role in the propagation of shocks. With markups, and therefore profits, GDP movements are not only tied to changes in aggregate technology and the associated reaction in factor supply, as in the perfect competition standard models.

As noted previously by Hall (1988) and discussed in Basu and Fernald (2002) or Gopinath and Neiman (2014), price distortions introduce a wedge between marginal cost and the marginal product of inputs implying that changes in intermediate input usage has a first order impact on GDP, over and beyond changes in technology and factor supply. The intuition for this abstract statement goes as follows: with markups, value added computed by statistical agencies is not simply equal to factor payment but also includes profits. Hence, even a country with a perfectly inelastic supply of domestic factors and a constant technology could experience GDP movements, for example if profits change.

When interpreting GDP fluctuations through the lenses of a structural model with perfect competition, these profit fluctuations could easily be mistaken for a “non-technology shock” (Huo et al (2019))— in the sense that they “explain” GDP movements over and beyond changes that are due to technology shocks and the associated reaction in factor supply. However, such interpretation is misleading as it implies that the reason countries have correlated GDP is that they are hit by correlated “non-technology shocks” and not because country-specific shocks are transmitted through trade linkages.

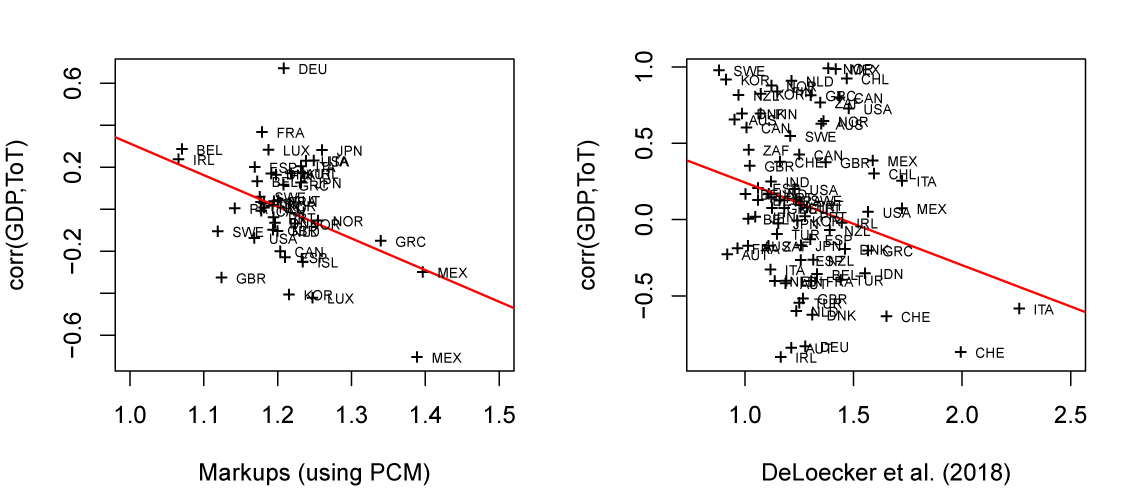

On the contrary, we argue the propagation channel can be rationalize through profit movements, and countries with larger markups are more sensitive to foreign shocks (as measured by terms-of-trade fluctuation). In figure 2, larger markups is associated with a larger GDP decline following a terms-of trade shock (which can be thought of as a proxy for foreign shocks).

Figure 2: Higher markups associated with a lower correlation between terms of trade and GDP fluctuations

Controlling for various unobserved factors, our empirical findings emphasize the role of competition distortions to understand an economy’s sensitivity to foreign shocks. In our simulations, reducing markups to zero significantly reduces GDP co-movement (table 1). This finding is increasingly relevant considering recent debates on the rise of market power all around the world (De Loecker and Eeckhout 2018, Díez et al. 2019).

Table 1: Comparison between data and model simulation, with sensitivity analysis on the role of markups

| Increase in bilateral GDP correlation associated with a 1% increase in trade proximity in inputs | Increase in bilateral Solow Residual correlation associated with a 1% increase in trade proximity in inputs | |

|---|---|---|

| Data | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| Benchmark model (markups = 25%) | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Markups reduced to 0 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Markups reduced to 20% | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Markups increased to 33% | 0.08 | 0.06 |

Extensive margin adjustments

Moreover, fluctuations along the extensive margin have the potential to create an additional amplification mechanism between domestic productivity and foreign shocks. As noted by Gopinath and Neiman (2014), love of variety is a form of increasing returns to scale: a firm with more suppliers is more efficient at transforming inputs into output, which leads to an increase of value added over and beyond domestic factor supply variations.

Solow residuals and aggregate technology

Together, market power and extensive margin adjustments create a link between foreign shocks and measured domestic productivity (as measured by Solow Residuals (SR)) and, with these features, there is a misalignment between SRs and true aggregate technology.

Both in the data and in our simulations, countries with high markups are characterized by a strong relationship between shocks to their trade partners and domestic Solow Residual fluctuations. In the data, an increase in trade is also significantly associated with an increase in Solow Residual correlation (we call this association the Trade-SR slope). While our benchmark model reproduces a realistic trade-SR slope, this association is absent in a version without markups and extensive margin adjustments (table 1).

The main point is that since SR measures the change in GDP that is not explained by movements of capital and labor fluctuations, it does not only capture changes in technology, but also captures fluctuations of profits and adjustments along the extensive margin. While international correlation of Solow Residual is close to 25%, we estimate technology co-movement to be less than 19%. The difference simply reflects the endogenous synchronization of SR through trade, due to profits and extensive margin movements. SR is also much more volatile and less auto-correlated than technology, which means it is a poor proxy for calibrating technology shocks.

Table 2: Average correlation of GDP and Solow Residual in the data and different simulations

| Exact Aggregate Technology | GDP Correlation | Solow Residual Correlation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data | — | 0.27 | 0.23 |

| Benchmark model (markups = 25%) | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.25 |

| Markups reduced to 0 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.20 |

| Markups reduced to 20% | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.23 |

| Markups increased to 33% | 0.19 | 0.31 | 0.28 |

References

- Arkolakis, Costas and Ananth Ramanarayanan (2009) “Vertical Specialization and International Business Cycle Synchronization”, The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Vol. 111, pp. 655–680.

- Basu, S. and J. G. Fernald (2002) “Aggregate productivity and aggregate technology,” European Economic Review, Vol. 46, pp. 963–991.

- De Loecker, J and J Eeckhout (2018), “Global Market Power”, NBER working paper 24768.

- De Soyres, F. and Gaillard, A. (2019a). “Value added and productivity linkages across countries”. FRB International Finance Discussion Paper No.1266.

- De Soyres, F. and A. Gaillard (2019b), “Trade, Global Value Chains and GDP Comovemement: An Empirical Investigation”, Working Paper.

- Díez, F, J Fan, and C Villegas-Sanchez (2019), “Global Declining Competition”, CEPR discussion paper DP13696.

- Frankel, J. and A. Rose (1998) “The Endogeneity of the Optimum Currency Area Criteria”, Economic Journal, Vol. 108, pp. 1009–25.

- Gopinath, G. and B. Neiman (2014) “Trade Adjustment and Productivity in Large Crises,” American Economic Review, Vol. 104, pp. 793–831.

- Hall, R. E. (1988) “The Relation between Price and Marginal Cost in U.S. Industry,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 96, pp. 921–47.

- Huo, Z, A A Levchenko, and N Pandalai-Nayar (2019), “The Global Business Cycle: Measurement and Transmission”, CEPR Discussion Paper no. 13796.

- Imbs, J (2004), “Trade, Finance, Specialization, and Synchronization”, Review of Economics and Statistics, 86 (3), 723–34.

- Johnson, Robert C. (2014) “Trade in Intermediate Inputs and Business Cycle Comovement”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 6, pp. 39–83

- Kehoe, T. and K. Ruhl (2008) “Are shocks to the terms of trade shocks to productivity?” Review of Economic Dynamics, Vol. 11, pp. 804 – 819.

François de Soyres (2019). “Increasing Business Cycles Synchronization: The Role of Global Value Chains, Market Power and Extensive Margin Adjustments,” FEDS Notes. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, December 13, 2019, https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.2489.