From theory to practice

In 1962, economist Paul Samuelson showed that using standard economic assumptions, time diversification is a mathematical fallacy. In other words, the idea that investors should hold relatively safe assets for short-term goals and riskier assets for long-term goals is false. According to Samuelson, if you've favored stocks for 40 years, you'll probably favor them just as much in a month.

Subsequent researchers have denied, but not disproved, Samuelson's findings, but they continue to be ignored. Like other investment websites, Morningstar regularly publishes articles that assume time diversification. Investment professionals also do so when constructing their portfolios. For example, all Target Date 2050 funds hold more stocks than Target Date 2025 funds.

I'm not writing this to argue against common practice; I agree with it. (I'll argue why next week.) My point is to acknowledge the existence of Samuelson's argument. Ultimately, it doesn't convince me. But if it does convince you, the material presented in this article is irrelevant. I'll warn you in advance.

Duration: 1 year

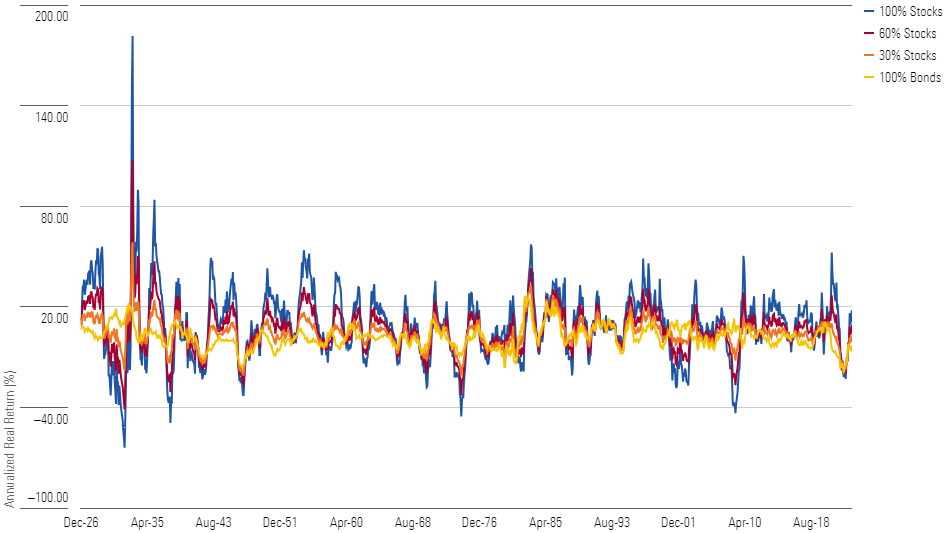

This column contains four charts, each showing the same information over a different period of time. They show the inflation-adjusted returns since January 1926 for four portfolios: 1) 100% large U.S. corporate stocks, 2) 60% stocks and 40% intermediate-term U.S. Treasury bonds, 3) 30% stocks and 70% bonds, and 4) 100% bonds. The first chart, showing one-year results, should look familiar.

But I had to look at that first blue line a third time: Yes, stocks made an inflation-adjusted 180% gain in the 12 months from July 1932 to June 1933. Unfortunately, stocks lost money in five of the next eight years.

Here are the summary statistics: The table shows how often the 100% stock portfolio outperformed the other three portfolios. It also shows how often each investment suffered double-digit losses (again, returns are in real terms).

One Year Overview

Surprisingly, at least for me, stocks earned essentially the same margin of victory against each of the three alternative portfolios. I expected bonds to perform best, but the percentage of double-digit losses was in line with my expectations. The higher the proportion of bonds in your portfolio, the better your chances of avoiding that fate.

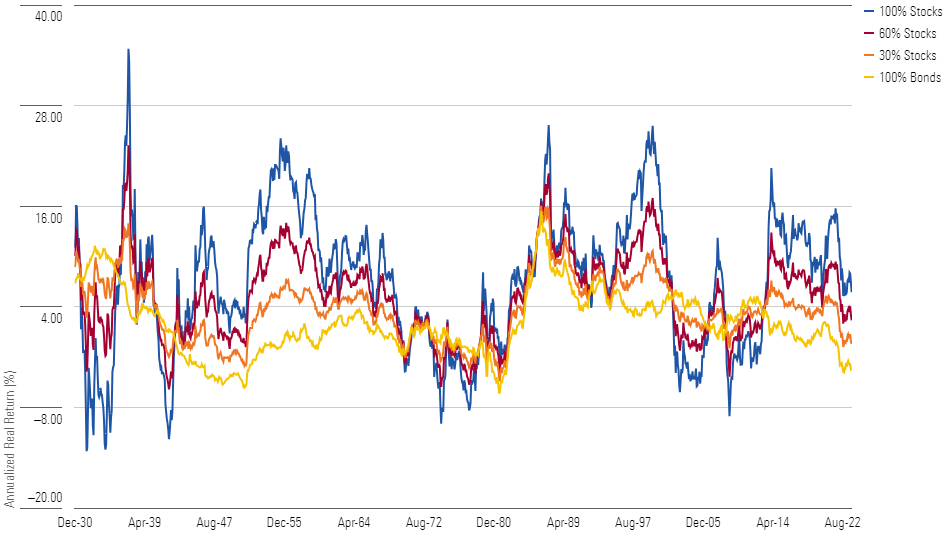

Duration: 5 years

This chart looks different. The blue line, which represents a 100% stock portfolio, has continually moved up and down on the one-year chart, but never consistently led or lagged the other lines, but the five-year chart shows some patterns. The blue line was below the other lines for quite some time during the Great Depression, but was above the other lines for long periods of time in the 1950s, late 1990s, and 2010s.

But overall, the results are similar to those for the one-year period. The win rate for the 100% stock portfolio increased slightly, but not by much. Again, this portfolio had double-digit losses one in six times. (This calculation, like the 10- and 20-period calculations, is cumulative, meaning that to be in the loss column, the return over the period must be less than -10%, not that the return is an annualized amount.)

Five-Year Overview

The only surprise, and disappointment, is that a 100% bond portfolio experienced double-digit losses over 13% of periods, compared with just 3% in any single year. This is bad news for bond investors because problems in the bond market tend to be clustered rather than random.

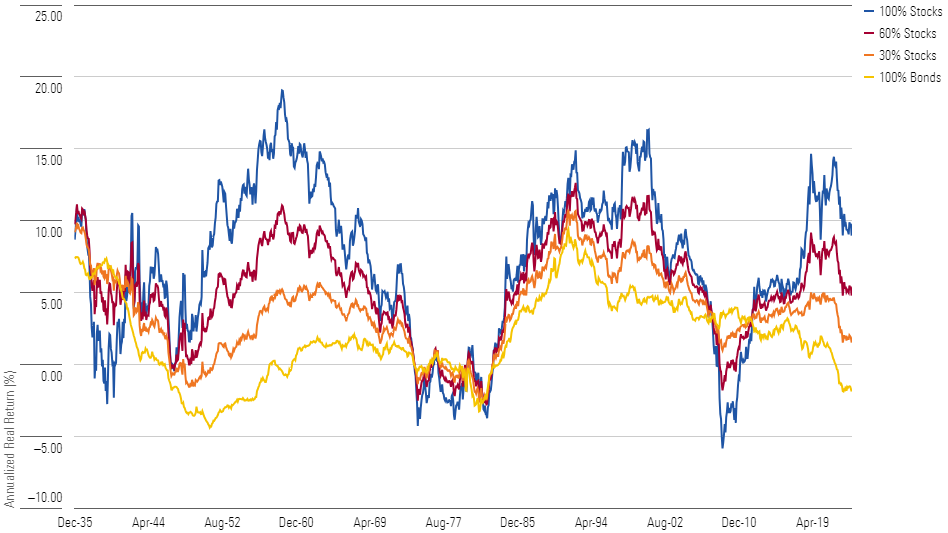

Time range: 10 years

The picture for stocks clearly brightens when we expand the time period to 10 years. The blue line is above the other lines for long periods, including the 25-year period. Conversely, it is slightly below the other lines for three periods separated by several decades.

Summary statistics for 100% stock portfolios have also progressed, but the improvement is incremental: The portfolio's winning percentage has risen to about 80%. This is impressive, but it also shows that in one decade out of five, investors would have been better off mixing in bonds or (less commonly) not buying stocks at all.

Summary of the Decade

Not that the latter choice was a wise one: Over a 10-year time frame, bonds were replaced by stocks as the portfolio most likely to lose at least 10% of its value. 100% stock portfolios suffered the biggest losses at the worst times, while 100% bond portfolios experienced double-digit declines.

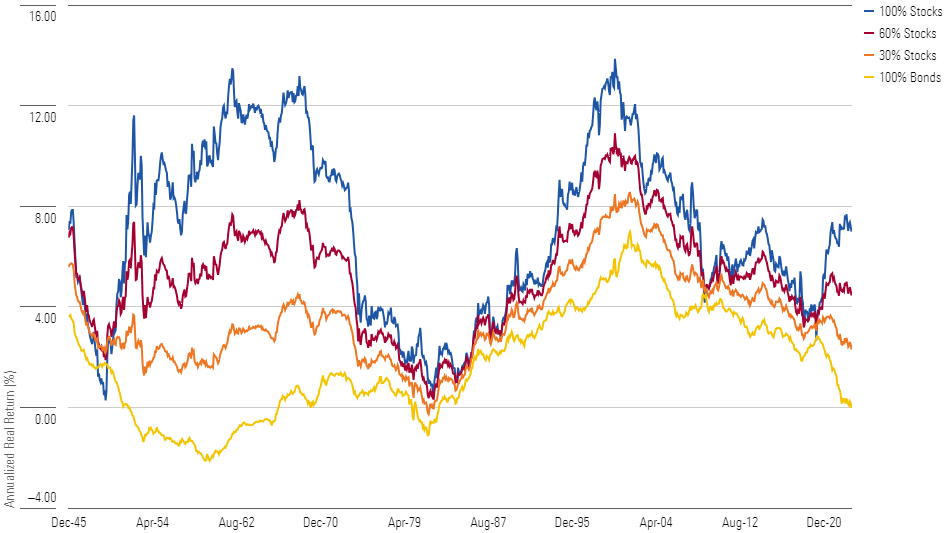

Time Horizon: 20 Years

Extend the time period to 20 years and the contest is over. Since the very early observations incorporating the Great Depression, 100% stock portfolios have almost always outperformed other portfolios, often by a large margin. Even a cursory glance at the chart leads to the conclusion that the blue line is far superior.

Summary statistics support that impression. (Not that we can deny it; this chart really does paint the full picture.) Diluting a stock portfolio with bonds reduces total returns 93% of the time when bonds have a moderate holdings, 97% when bonds have a large holdings, and a whopping 99% of the time when bonds substitute for the entire holdings.

Summary of the past 20 years

Over 20 years the risk assessment is reversed. Bonds are the real danger and, when inflation is taken into account, routinely suffer double-digit losses. The safe bet is stocks. With 30% of your portfolio in stocks you will never have a cumulative loss of more than 10%, but there have been several cases where a 30% stock portfolio has lost purchasing power over 20 years. But when stocks make up 60% or all of the portfolio, there are no losses. Historically, neither a balanced nor a 100% stock portfolio has ever been in the red over a rolling 20-year period. They have always made at least a 10% gain. something.

The opinions expressed here are those of the author. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a wide range of perspectives.